Kierkegaard and Radical Discipleship:

A New Perspective

by Vernard Eller

(continued)

PART II: THE DUNKERS AND THE DANE

III. The Problem of Sociality

Nobody wants to be this strenuous thing:

an individual; it demands an effort.

But everywhere services are readily offered through

the phony substitute: a few! Let us get together

and be a gathering, then we can probably manage.

Therein lies mankind’s deepest demoralization.1

Spiritual superiority only sees the individual.

But, alas, ordinarily we human beings

are sensual and, therefore,

as soon as it is a gathering, the impression changes–

we see something abstract, the crowd,

and we become diflerent.2

In giving to den Enkelte and its characteristics as dominant an emphasis as the foregoing chapters indicate he did, S.K. inevitably created a major problem, the problem of sociality. How is man to be understood and handled in his social relationships? If religion is essentially a matter of den Enkelte before God, at what point do “others” come into the picture? Can den Enkelte in any sense join with or be joined to them without jeopardizing his own status as den Enkelte?

Obviously, S.K. will give attention to one type of sociality that is inimical to den Enkelte, a sociality which acts precisely as an escape from or substitute for the strenuous thing of being den Enkelte. Such groupings S.K. named “the crowd”; and his polemic against the crowd and crowd mentality was loud, bitter, and abundant. In one respect he even made it his first task to attack the crowd, for only by dissolving it could he get to individuals with his concept of den Enkelte.3

Within S.K.’s frame of reference, “the crowd” was an absolutely negative concept; it is “the Evil,” as he called it,4 the sworn enemy of den Enkelte. And the same negativity was attributed to the corollaries of “the crowd,” which are:

- “the public”;

- “the press,” i.e. journalism, the instrument through which “the public” both expresses and creates itself;

- “the world,” in its technical, New Testament sense; and

- “the Establishment,” which, we shall see, is tantamount to “church” in that its established character is the hallmark of the churchly concept.

S.K. allowed no place at all for crowd sociality; and because of the emphatic and pervasive character of his invective, many students have read him as renouncing all sociality whatever. Martin Buber is the prime example of such an interpreter, and his stature as one of the ranking theologians who best understood S.K. makes his charge all the more serious. It behooves us to give the matter very careful consideration.

Buber opened his essay on S.K. with the following paragraph, which includes what we will contend is a gross misunderstanding:

Only by coming up against the category of the ‘Single One’ [den Enkelte], and by making it a concept of utmost clarity, did Søren Kierkegaard become the one who presented Christianity as a paradoxical problem for the single ‘Christian.’ He was able to do this owing to the radical nature of his solitariness. His ‘Single One’ cannot be understood without his solitariness, which differed in kind from the solitariness of one of the earlier Christian thinkers, such as Augustine or Pascal, whose name one would like to link with his. It is not irrelevant that beside Augustine stood a mother and beside Pascal a sister, who maintained the organic connexion with the world as only a woman as the envoy of elemental life can; whereas the central event of Kierkegaard’s life and the core of the crystallization of his thought was the renunciation of Regina Olsen as representing woman and the world.5

And as he continued, Buber pressed this point to the extreme:

This relation [between den Enkelte and God] is an exclusive one, the exclusive one, and this means, according to Kierkegaard, that it is the excluding relation, excluding all others; more precisely, that it is the relation which in virtue of its unique, essential life expels all other relations into the realm of the unessential.6

Kierkegaard does not marry … because he wants to lead the unbelieving man of his age, who is entangled in the crowd, to becoming single, to the solitary life of faith, to being alone before God.7

This is how Buber read S.K., and it is not extravagant to suggest that one of Buber’s motives in writing I and Thou was to correct the solitariness of S.K.’s den Enkelte. Buber himself, in contrast to S.K., would incorporate sociality as an integral aspect of den Enkelte:

God wants us to come to him by means of the Reginas he has created and not by renunciation of them….8

The Single One corresponds to God when he in his human way embraces the bit of the world offered to him as God embraces his creation in his divine way. He realizes the irnage when, as much as he can in a personal way, he says Thou with his being to the beings living around him.”9

And his summation reads:

‘The Single One’ is not the man who has to do with God essentially, and only unessentially with others, who is unconditionally concerned with God and conditionally with the body politic. The Single One is the man for whom the reality of relation with God as an exclusive relation includes and encompasses the possibility of relation with all otherness, and for whom the whole body politic, the reservoir of otherness, offers just enough otherness for him to pass his life with it.10

Quite clearly Buber has chosen the better part–if he has represented S.K.’s part fairly. We contend that he has not. We would not endeavor entirely to absolve S.K. of a certain deficiency of emphasis which at least makes possible the reading Buber gives him. However, we will maintain: first, that a positive doctrine of sociality is not lacking in S.K. Although perhaps insufficiently stressed, it is present as a real, integral, and even necessary part of his concept. Second, although not as well emphasized, the social aspect actually is better structured in S.K. than in Buber. Buber does little more than asseverate that all man-to-man relationships are encompassed in the man-to-God relationship. S.K. analyzed sociality in more detail and made it integral to his thought as one pole of a dialectic.

There is a further distinction in the ways that S.K. and Buber treat sociality; it is subtle and almost impossible to document, but it may be of profound significance nonetheless. Buber starts with man-to-man and man-to-nature relationships and builds them up toward the man-to-God relationship. The man-to-God relationship becomes the consummation and sum of human relationships. Of course, the sum is greater than the parts and ultimately is to be seen as the source of the parts; but basically it is through our experience with other thous that we come to know the Eternal Thou. “God wants us to come to him by means of the Regina: he has created….” And the book I and Thou is organized over precisely this pattern.

It will shortly become evident, however, that S.K.’s thought proceeded conversely. He began with the God relationship and derived all human relationships from it; it is only from God and with the help of God that one can discover his neighbor at all. And S.K.’s approach would seem the more accurate, at least for Christian thought. Actually, S.K. anticipated the possibility of criticism such as Buber’s and tried to forestall it:

In spite of everything men ought to have learned about my maieutic carefulness, in addition to proceeding slowly and continually letting it seem as if I knew nothing more, not the next thing–now on the occasion of my new Edifying Discourse they will presumably bawl out that I do not know what comes next, that I know nothing about sociality. The fools! Yet on the other hand I owe it to myself to confess before God that in a certain sense there is some truth in it, only not as men understand it, namely that always when I have first presented one aspect sharply and clearly, then I affirm the validity of the other even more strongly. Now I have the theme of the next book. It will be called Works of Love.”11

S.K.’s “confession before God” gets at both the truth and the falsehood of Buber’s reading. Kierkegaard’s life was not socially normal. As a genius in a provincial town he was bound to feel somewhat isolated; as a melancholy genius it was inevitable that he live as one apart. It is true that he never married, that he never (at least alter he broke with his father) had any truly intimate companions, that he never belonged to any group that afforded him first-hand experience of true Gemeinschaft. This personal deficiency undoubtedly is one reason why S.K. did not give more attention and emphasis to a doctrine of sociality, although an equally valid explanation could be that the need of his age was first for a concept of individuality before a social emphasis could be properly understood. Nevertheless, it is almost certainly this personal deficiency that S.K. meant as being confessed before God.

But even this deficiency ought not be exaggerated; there are some facts that stand on the other side. Particularly as a young man, S.K. was something of a social butterfly. He moved in the top circles of Copenhagen society; as a wit and bon vivant, his presence was valued on social occasions; he was a connoisseur of the theater, music hall, and dinner table. Throughout his life he maintained these connections to some extent and was an acquaintance of the leading social, civic, and religious figures of Denmark. Also, at least until the time that the Corsair incident drove people away from him, S.K. cultivated many speaking friendships with the common people on the street. He made it a point to converse with, counsel with, and offer help to servants, peasants, workingmen, people from any and all classes of society. And although S.K. was not a husband and father, he was an uncle par excellence; his nieces and nephews knew him as an especially loving and interesting friend of children. The people who actually rubbed shoulders with S.K. would be hard put to recognize Buber’s stark description of one who had renounced all bonds with the world. It is true that none of these relationships were of the deepest, most intimate sort, yet it is grossly unfair to make S.K. out as simply and obviously a “solitary.”

But such evidence quite aside, it is even more unwarranted to use S.K.’s personal life as the key for interpreting his thought, particularly when S.K. made it clear that he was well aware of his personal abnormalities and was striving continually to compensate for them. Above all, S.K.’s renunciation of Regina is in no sense to be understood as a symbol of what S.K. required of den Enkelte; whatever its meaning, that break was of purely personal significance, appertaining to Søren Kierkegaard and to Søren Kierkegaard alone. Certainly it was a renunciation of Søren Kierkegaard’s marriage but not by that token a renunciation of marriage per se. Fear and Trembling

was the book most directly molded by the Regina incident, in which S.K. meditated on his renunciation under the figure of Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac, but the sacrifice is there presented as the absolutely exceptional

demand, in deliberate contradistinction to universal obligation. Kierkegaard did not break with Regina as a representation “in concrete biography of the renunciation of an essential relation to the world as that which hinders being alone before God,” and most certainly he did not then “express it as an imperative: let everyone do so.”12

Because it was Buber who initiated a contrast between S.K. and Augustine, perhaps we are justified in tracing the comparison more closely. The parallel is actually much nearer than Buber guessed and the conclusion quite different from that at which he arrived. The counterpart of Monica (Augustine’s mother) is not Regina but S.K.’s father Michael. In both cases there was a deeply devout parent “praying” a prodigal son back to Christianity. In both cases there was a joyous reconciliation with God and with the parent in God-Augustine at the age of thirty-three years, S.K. twenty-five. In both cases the parent died but very shortly after the reconciliation took place. In both cases the sons entered their illustrious careers some three or four years after their “conversions” (Augustine did not have a mother standing beside him during his career as a Christian). In both cases the conversion was accompanied by the “renunciation” of women of intimate association. Before his conversion Augustine had sent away the mistress with whom he had lived for some years and by whom he had had a son–this in preparation for a respectable marriage. At the time of his Conversion Augustine sent away a second mistress–this in preparation for Christian celibacy. S.K. both made and broke his engagement to Regina within approximately a three year period following his conversion.

Both “renounced” women; the difference in the way they did this is instructive, although the instruction is not at all what Buber suggests. Augustine left his two mistresses in the interest of achieving his own sainthood, the first in order to become acceptable in the eyes of men, the second in the eyes of God. In his Confessions Augustine showed extreme concern over his own sinfulness and his desire for holiness, but he showed nothing of a comparable concern over his responsibility to these women with whom he had loved and lived, no particular concern over what happened to them, over what his renunciation did to them.

With S.K. the case was very different. Although it probably never will be made completely clear just why S.K. felt that it was God’s will for him to break his engagement, there is no evidence that he understood it as a way of enhancing his own saintliness; it is clear that he was as much or more concerned for Regina as for himself, that the break was as much for her sake as for his own. Consequently S.K. was quite willing to play the role of devil rather than saint in order to ease her suffering; and one gets the feeling that he actually would have been willing to have been lost in order to ensure her salvation.

There were, of course, differences of circumstance, social mores, et al., between the action of Augustine and S.K., and we have no intention of running down Augustine. But completely contrary to Buber, if with either man the event was the crystallization of a sweeping and doctrinaire renunciation of “women and the world,” patently it was more so with Augustine than with S.K.

However, the fundamental error of those who would interpret den Enkelte as being entirely solitary is the misimpression that S.K.’s fulminations against “the crowd” necessarily included all sociality. A more precise view of his terminology will enable us to correct this misunderstanding and will open to us new vistas of his thought.

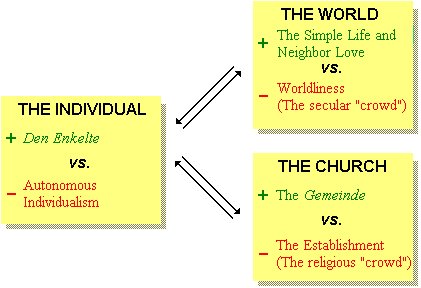

The key–which is always the one to try with S.K.–is dialectic. And regarding this problem of sociality, we find precisely the same pattern as was described earlier in connection with “inwardness and obedience,” “faith and works.” In this instance the relationships are somewhat more complex, and a diagram may help clarify the discussion.

The first pole of the dialectic is represented at the left. Den Enkelte, of course, is the positive, religious concept of individualism as affirmed and promoted by S.K. The negative perversion, the contradictory–which is to be utterly rejected–is autonomous, self-asserting “individualism” (which S.K. identified and rejected as being of the Aesthetic Stage). The other pole of the dialectic is represented at the right; it includes all sociality, any and all human associations for whatever purpose, constituted in whatever mode, on whatever principle. S.K. saw, however, that these can and should he divided into two distinct types. One social type is The World, using that term in the broadest possible sense to cover all associations except those of the church. The other social type is The Church, using that term also in the broadest possible sense to cover all associations of a religious nature. It would be wholly accurate to term these as Secular Sociality and Religious Sociality–except for the implication that therefore “secular” relationships lie outside the purview of religion. S.K. contended that one’s life in the World must be lived before God just as certainly as his life in the Church; there is no distinction on this score. The distinction is, rather, that whereas the Church is constituted of man-to-man relationships for the sake of God, the World is constituted of man-to-man relationships for the sake of man; the primary orientation of the Church is vertical, that of the World, horizontal; a Christian’s relationships of the World are derived from his prior relationship to God, whereas his relationships of the Church exist for the sake of his relationship to God.

Religious and secular sociality are different enough to call for individual treatment, and each forms its own distinct dialectic with den Enkelte. Under The World, the positive which S.K. affirmed consists of “The Simple Life,” dealing with the world of nature and things, and “Neighbor Love,” dealing with the human world of other persons. Opposed to this is the negative, the perversion, which is “Worldliness,” or “Conformity to the World.” The concept “crowd” includes the negative socialities of both the secular and the religious sphere; “crowd mentality” is what S.K. found to be the distinctive feature both of the World and the Establishment.

Admittedly, we have encountered terminological difficulty at this point. The word “world” properly can he used with three mutually exclusive meanings. In the diagram, “the world” is an inclusive, nonevaluational term, although it is common usage thus to divide all of life between the Church and the World. But in the positive and the negative items subsumed under this “world” are two more “worlds” which complicate the situation no end. Here is found the contradiction between “the world” (positive) which God so loved that he gave his only Son (John 3:16) and “the world” (negative) which for us to love is proof that the love of the Father is not in us (1 John 2:15). These two “worlds” lie in even closer proximity in the sectarian shibboleth derived from John 17:16 and 18, i.e. “in the world but not of the world.” “In the world” cannot mean merely “physically extant”; that would be too obvious to be significant; a Christian is not called to live in the world in this sense–he cannot help himself. No, the world the Christian is to be “in” is the world of “other people.” The apostle who in one chapter of his epistle exhorted Christians not to love the world exhorted them in the succeeding chapter to love everyone in the world (1 John 2-3). And to love this world of people–an obligation which S.K. took very seriously–is, of course, to be related to them, to be a part of it.

On the other hand, the world which the Christian is not to be “of” is the world of goals and values as determined by the secular society which is not oriented toward the will of God. In short, one can love, accept, and identify with those who make up society without loving, accepting, or identifying with the standards of that society. The Christian can reject the evaluation men put upon things, thus rejecting both “the things of this world” and the possibility of being “a man of the world,” without rejecting either “the world of things” or “the world of men.” The distinction is a rather easy one to understand–a very difficult one to live. But because human language is not precise, S.K. explicitly could renounce and denounce the world, Martin Buber could come along later and accuse S.K. of renouncing the world, and yet what Buber says can be a grave misunderstanding. We intend to show that S.K.’s strictures against “the world” are an instance of condemning only crowd sociality and thus by no means should be taken to imply solitariness and the rejection of all sociality.

Likewise, under the heading The Church, the positive is “the Gemeinde” and the rejected negative is “the Establishment.” Also, as above, terminological confusion again shows itself. The “church” heading is a very broad and entirely neutral concept. The negative “church” is used in a “churchly” sense, as over against “sect.” But in another sense, the positive Gemeinde is just as validly a church as any of the “churches” are.

The arrows on the chart illustrate the point that we have made earlier, that the dialectic relationship holds only between complementary positives; the intention is that the negatives be cancelled and obliterated.

There is a further observation regarding the dialectic pattern that holds equally true with our earlier examples as well as with this one. A real source of the power and efficacy of a dialectic lies in the fact that the positive of one pole stands precisely as the preventative or corrective of the negative of the opposite pole. Thus in the present instance a concept of den Enkelte is the cure for crowd mentality; and simple living, neighbor love, and Gemeinschaft are the cures for autonomous pretension. And thus in the earlier case obedience is the cure for either hiddenness or superficial emotionalism; and inwardness is the cure for works-righteousness.

Finally, the chart plots the sequence for this portion of our study. The present chapter has set the problem; Chapter VIII will treat the positions of S.K. and the Brethren regarding “world-negative”; Chapter IX, “world-positive”; Chapter X, “church-negative”; and Chapter XI, “church-positive. ” Each chapter should be read in relation to the pattern as a whole.

1 Rohde Journals, 129 (1854).

2. Ibid., 127 (1850).

3. Purity of Heart, 143-44.

4. Point of View, 61.

5. Martin Buber, “The Question to the Single One,” in Between Man and Man, 40.

6. Ibid., 50.

7. Ibid., 59.

8. Ibid., 52.

9. Ibid., 56-57.

10. Ibid., 65.

11. Papirer, 8:1:A:4 (1847), quoted by the translators Howard and Edna Hong in their introduction to S.K.’s Works of Love, 15-16. The Hongs themselves cornment: “Those who say that Kierkegaard had no consciousness of anything but a purely private individualistic ethic cannot digest this work [Works of Love], nor, when properly understood, his other ethical works, but least of all this.”

12. Buber, Between Man and Man, op.cit., 58, 55, respectively

IV. The World Well Lost

a. Nonconformity to the World

To keep oneself pure and unspotted from the world

is the task and doctrine of Christianity–

would that we did it. 1

What was said in paganism and Judaism,

that to see God is to die,

or at least to become blind or dumb

and the like, is expressed ethically in Christianity as a task:

to die to the world

is the condition for seeing God. 2

Woe, woe to the Christian Church

if it would triumph in this world, for then it is not

the Church that triumphs, but the world has triumphed.

Then the heterogeneity of Christianity and the World

is done away with, the world has won, Christianity lost.

… And the day when Christianity

and the world become friends

Christianity is done away with. 3The actual phrase “nonconformity to the world” (based on Romans 12:2) is not Kierkegaardian nor is it found in eighteenth century Brethren literature. In the nineteenth century it became the technical term by which the Brethren identified their doctrine, although by this time the doctrine itself had deteriorated until its primary emphasis was a legalistic prescription of a standard mode of dress and its secondary emphasis the legalistic prohibition of such things as jewelry, dancing, and card-playing. However, eighteenth century writings do not display this narrow moralism and do not so much as mention the wearing of a peculiar garb. The nineteenth century had the term, but the eighteenth century had much the better understanding of its meaning.

The closest the eighteenth century Brethren came to using the phrase itself was in a “big meeting” (probably the regular Annual Meeting of 1791) reported in the diary of Mack Junior. The principal query brought to that gathering was: “How could one, here in Germantown, resist by a united effort the very injurious evil which by conformation to the world is wrought upon the minds of the young, as we are living so near to the capital of the country.”4 Yet it is plain that the doctrine itself was part of Brethrenism from the beginning. Mack Senior had written: “This body or church is separated from the world, from sin, from all error, yes, from the entire old house of Adam-that is, according to the inner part of faith…. However, this body or the church of Christ still walks outwardly in a state of humiliation in this wicked world.”5

A prominent corollary of nonconformity–mentioned here by Mack and to be closely paralleled by S.K.–is that in contrast to the life of the world the life of the Christian is a state of humiliation.” This point was made with more emphasis in a hymn by John Price:

Let us, with lot, flee "the Sodom of this world."...

Let us not act as does the world

But seek only to he despised.

Let us not question this;

Let us look to heaven

And despise the tumult of the world,

Accepting all the disgrace.6

Nonconformity was a particularly strong theme with Michael Frantz.7 But it was Sauer Junior who picked up a little different facet of the belief, this dealing with the Christian’s relationship to worldly government. The Sauers felt obliged to include in their almanacs the court calendar for the year; they also felt obliged to accompany that calendar with a little poem making it plain that the courts were no place for a Christian to be found. We presume that Sauer Junior himself was the author of the one for 1767:

[Christians] must, as [Christ's] servants,

Proceed here according to His example

And highly honor His practices

And claims, and stand within them.

Therefore they cannot become citizens

Here in this vale of misery,

Because they are ransomed from the earth

Through a great election of grace....

They let cloak and mantle go,

And rather do without clothing

Than in their years as pilgrims

Mingle in the quarrels of the citizenry....

They have never in anything opposed

The authorities who are appointed....

They will not readily sue anyone....

In poverty, shame, ridicule, and derision,

[The Christian] is known for his patience.

The citizens of this world and time

Can never he peaceful for long;

Their self-interest teaches them to fight and quarrel;

They will have their rights and splendor.8

There are here several ideas that merit comment. Nonconformity follows as a direct corollary of Nachfolge, the imitation of Christ; this connection will show up as clearly in S.K. as in the Brethren. The Christian’s life on earth customarily is typified in some such terms as “this vale of misery”; this is as true with S.K. as with the Brethren, although in neither case is it accurate to assume that this judgment leads to a “joyless” concept of the Christian faith. The note about the Christian not opposing appointed authorities is a very typical Brethren theme, actually an emphatic ingredient of the very doctrine of nonconformity. The Christian is to live above the law, and when the law would require him to do something contrary to the will of God he is to defy that particular law, but he has absolutely no intention of undermining the principle of law itself or questioning the right of secular authority to govern the world and to govern him to the extent that he is in the world. But the principle of the world is “self-interest,” the struggle for one’s own rights and privileges, and of this the Christian wants no part.

It was Mack Junior who picked up another basic point of contrast between the Christian and the world, the complete divergence as to what is valued as “treasure”:

Say, what is richer

Than the poverty

Which an the cross in Jesus' wound.

By the thief was found?

Christ's poverty

Makes us rich and free!

But whoever still tarries

With the treasure of the world,

He cannot find this treasure.9

And Jacob StoIl put the thought into stark and eloquent terms when he wrote:

Nothing is the lust of the world; nothing is the world;

Nothing is honor; nothing is gold;

Nothing are the dazzling things of this world--

Often they make the eyes dark.10

Kierkegaard, for his part, drove deep the cleavage in terms as intransigent as any used by the Brethren:

‘He must either hate the one and love the other, or he must hold to the one and despise the other.’ Consequently love to God is hatred to the world, and love for the world is hatred toward God; consequently this is the tremendous issue–either love or hate. Hence this is the place where the world’s most terrible conflict is to be fought. And where is this place? In a man’s heart.11 [Cf. Cf. S.K.’s words quoted above]

But, it immediately will be objected, there is a great difference. No matter how S.K. be quoted, it is quite obvious that, in sharp contrast to the simple Brethren, he was in many ways a prime example of worldly sophistication, as he said of himself, possessing “intellectual gifts (especially imagination and dialectic) and culture in superabundance.”12 There is no denying that S.K. was such a person. His everyday mode of life was what men of the world would call “gracious,” what the Brethren would have called “luxurious.” In matters of art, music, theater, philosophy, learning–culture, in short–he was a crowning achievement of Society, a “humanist,” a Christian humanist par excellence. This aspect of S.K. is conspicuous, and it is clearly the case that many students have been drawn to him precisely because of his urbanity and sophistication: here is a model of culture and Christianity united in an attractive combination where each complements and enhances the other.13 Walter Lowrie–who at this point definitely seems to be creating Kierkegaard in his own image–waxes eloquent about S.K.’s culture, concluding:

He remained a Humanist when he became a serious Christian, and for this reason, he was essentially a Catholic, as Father Przywara recognizes. And for this very reason Barth rejected him. It was owning to his Humanism that he disdained every sectarian movement however zealous.14

Whether Lowrie fully understood Przywara and Barth is a question that need not detain us, and for the high Anglican Lowrie to find both humanism and Catholicism attractive in S.K. is not particularly surprising, but the question as to whether S.K. actually was a “humanist” demands the most careful consideration.

The very concept “humanism” is an ambiguous one and needs to be defined. Humanism can imply simply a deep concern for human welfare. In this sense Christianity is itself “the true humanity,” as S.K. suggested; and he, along with every other Christian, was essentially a humanist. This, obviously, is not what Lowrie has in mind. In another sense, humanism is a faith, an alternative to Christianity that finds life’s ultimate values not in God but in human achievement. In this sense neither S.K. nor any other Christian could be a humanist. Finally, and this certainly is what Lowrie intends, Christian humanism is the position of those who value human culture along with their Christian faith, who see cultural values as integrally related to the faith, indeed as a vital part of the faith. It is in this sense that S.K. is identified as a humanist and in this sense that we are concerned to deny the attribution.

Part of the difficulty arises through an illegitimate identification of S.K. with his pseudonyms. The pseudonyms were humanists, openly and avowedly such, and for that matter not even Christian humanists. But S.K. was not his pseudonyms; in fact the pseudonyms were designed for the express purpose that S.K. might delineate a position qualitatively lower than that with which he personally would identify. The humanism of the pseudonyms is beside the point as to whether Søren Kierkegaard was a humanist or not.

More of the difficulty stems from a too-easy reading of the fact that S.K. was cultured–without inquiring about the attitude in which he held that culture. A careful study will show that S.K. had these things “as though not,” as though he had them not.15 And because S.K. had these things “as though not,” because he attributed no real value or significance to them, he stands ideologically much closer to those who have them not than to those who do have them. The fact that he had all these “advantages” was, in S.K.’s own eyes, entirely incidental, worth nothing. As he saw it, the only real value of these gifts was that they enabled him to capture the attention of actual humanists that he might lead them out of humanism into Christianity. S.K. called himself “a spy in a higher service,”16 and he meant it with the utmost seriousness. He was not what he appeared, a man of the world; and it is tragic that the disguise has been taken for the real man.

S.K.’s most revealing statements in this regard cannot he fully appreciated unless one senses what Socrates meant to him. For S.K., Socrates represented the highest achievement of the human spirit; he stood as a symbol of the world at its best, the finest and noblest the world could offer. Kierkegaard was too modest to claim the following statement as his own) so he put it into quotation marks with a “so might the individual speak.” However, the translator Lowrie (undoubtedly correctly) identifies it as a personal profession of faith–yet ultimately it militates against any identification of S.K. as a humanist:

I have admired that noble, simple wise man of ancient times [Socrates]; … but I have never believed on him, that never occurred to me. I count it also neither wise nor profound to institute a comparison between him, the simple wise man, and Him on whom I believe–that I count blasphemy.

Would S.K. appreciate being treated in a volume entitled The Hemlock and the Cross?

As soon as I reflect upon the matter of my salvation, then is he, the simple wise man, a person highly indifferent to me, an insignificance, a naught.17

And what of the hemlock, specifically?

Lo, to be executed, humanly speaking, innocently, and yet die with a witticism on his lips, that is a proud victory, that is the triumph of paganism; and it is also the highest victory in the relationship between man and man, that is, please note, if God is left out, if all of life and its greatest scenes are still at bottom a game, because God does not participate; for if He is present, then life is earnest.18

When he deeply and seriously calls Socrates “a naught,” calls his heroic death “at bottom a game,” it seems apparent that culture in general never could stand high enough with S.K. to justify his being called a “humanist,” whether Christian or otherwise. “… Among those born of women no one has arisen greater…; yet the least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he” (Mt. 11:11)–this is not the stance of humanist.

The real Kierkegaard was an antihumanist, staging the most effective critique of humanism ever made–and that directed particularly against so-called Christian humanism. He declared in so many words that his own aesthetic accomplishments were a feint19 and evaluated the greatest of these in terms of the light it threw upon Christianity by way of contrast.20 His considered judgment of Christian humanism was stated with utmost clarity: “It is not difficult to see that culture makes men insignificant, perfects them as copies, but abolishes individuality.”21 “[The] culture and civilization [which Christendom has produced through the centuries] has at the same time produced a development of rational understanding which is in the process of identifying being a Christian with culture, and with intelligence, desirous of a conceptual understanding of Christianity. This is where the struggle must come, and will be fought in the future.”22 “Fought in the future,” S.K. said. Could it be that his critique has relevance when, under the aegis of an avant-garde concept of “secular Christianity,” there is a theological movement which rather consciously is feeling after a new liaison with sophisticated culture? And if so, is it not ironic that one of the names often invoked in this movement is that of Søren Kierkegaard?

S.K.’s concern hegan to show itself as early as Either/Or, not too appropriately in the very mouth of “A,” the aesthete:

This is part of the confusion which in our age asserts itself in so many ways: we look for a thing where we ought not to look for it, and what is worse, we find it where we ought not to find it; we wish to he edified in the theater, aesthetically impressed in church, we would be converted by novels, get enjoyment out of books of devotion, we want philosophy in the pulpit, and the preacher in the professorial chair23

S.K.’s later analyses were even more powerful:

In established Christendom the natural man has managed to have his own way. There is no endless contrast between the Christian and the worldly. The relation of the Christian to the worldly is conceived, at the most, as a potentialization (or more exactly under the rubric, culture), always directly; it is simply a direct comparative, the positive being civic rectitude…. One starts with the worldly. Keeping an eye upon civic rectitude (good-better-best) one makes oneself as comfortable as possible with everything one can scrape together in the way of worldly goods–the Christian element being stirred in with all this as an ingredient, a seasoner, which sometimes serves merely to refine the relish…. Christianity is related directly to the world, it is a movement without budging from the spot–that is to say, feigned movement.24 Men have confused Christianity in many ways, but among them is this way of calling it the highest, the deepest, and thereby making it appear that the purely human was related to Christianity as the high or the higher to the highest or the supremely highest. 25

It is a little difficult to understand why the author of such lines should be classed as a Christian humanist.

S.K. was concerned to condemn not only the coarse, blatant, repulsive sort of worldliness, but concentrated upon it in its most attractive and elegant forms–which he was convinced actually were the more sinister. Indeed, his critique would seem to constitute a blanket indictment of the world. In a sense it becomes that, but only because Christian values are so preeminent that all other values–which precisely is to say worldly values–come to be of evil in their tendency to attract or distract the ultimate loyalty of men. As S.K. put it:

[The world] is not absolutely evil, as it is sometimes passionately represented, nor is it untainted, but to a certain degree is both good and evil. But Christianly understood, this ‘to a certain degree’ is of evil.26

S.K.’s was not a blind rage against the world; he saw clearly that the issue was one of ultimate loyalty, and he pointed his charges at specific evils. Interestingly enough, some of the qualities he attacked are the very ones that many readers value highly in the writings of Søren Kierkegaard.

For one thing, the entire tenor and mood of polite culture is opposed to that of Christianity:

Christianity should never be communicated in the medium of tranquillity (unless the person who does it would dare to affirm that now all and every one are Christians). That is why being busy with art, poetry, philosophy, science and lecturing constitutes a sin in the Christian sense–for how dare I indulge myself pottering about with such things in peace and quiet?27

For another, S.K. would not be among those who in our day are so eager to look to the artists and literati as being unconscious, or at least incipient, prophets and theologians:

If, therefore, one occasionally presumes to understand his life with the help of the poet and with the help of Christianity’s explanation, presumes the ability to understand these two explanations together–and then in such a way that meaning would come into his life–then he is under a delusion. The poet and Christianity explain things in opposite ways.28

And for still another, S.K. despised the quality which shows signs of becoming dominant in some sectors of contemporary theology:

What the world most highly and unanimously honors is cleverness or acting cleverly. But to act cleverly is precisely the most contemptuous of all… To act cleverly is basically compromise, whereby one undeniably gets farthest along in the world, wine the world’s goods and favor, the world’s honor, because the world and the world’s favor are, eternally understood, compromise. But neither the eternal nor the Holy Scriptures have ever taught any man to go far or farthest of all in the world.29

The forthrightness, deliberate naivete, and simple honesty prized by the early Brethren would have appealed to S.K.

A very important element in S.K.’s thought was his social criticism, his insight into the dangers of technological and urban depersonalization, mass man, the tyranny of mob culture, etc. This part of S.K.’s message generally has been well heard and appreciated, and we need here note only that these insights grew out of his nonconformist viewpoint. But his basic position was thoroughly religious and Christian in character, and it is this aspect that is particularly germane to our study.

At heart, nonconformity to the world is simply the obverse of the doctrine of den Enkelte, for it is a person’s incorporation into the world crowd that prevents him from existing singly before God.30 Even so, although it is the world that keeps him from becoming den Enkelte, this is only because the man himself would have it that way.31 And thus the choice of refusing to be conformed to the world and the free venture of faith in which den Enkelte chooses himself before God–these two are one and the same choice. S.K. put the matter in one of his most moving passages:

A choice between God and the world. Do you know anything greater to set together for a choice! Do you know any more overwhelming and humbling expression for God’s indulgence and pardon towards man, than that He sets Himself, in a certain sense, on an equal line of choice with the world, merely in order to allow the man to choose? … If God has condescended to he that which may be chosen, then man must also choose–God will not suffer Himself to be mocked…. No one is to be able to say: “God and mammon, since they are not so unconditionally different, one may in his choice combine both”–for this is to refrain from choosing…. If anyone does not understand this, then it is because he will not understand that God is present in the moment of the choice, not in order to look on, but in order to be chosen…. But the right beginning begins with seeking the kingdom of God first; it begins therefore precisely with letting the world be lost.32

No matter how harsh S.K.’s diatribes against the world, no matter how complete his indictment of it, these proceed not from any sort of sadism, not from his melancholy, not from any judgment about the inherent evilness of the created world as such, but from a positive valuation of what God has offered in offering himself to man, then from a realization of the sort of absolute commitment and loyalty such an offer demands in response, and thus, finally, from the passionate hatred of anything that would obstruct such response. S.K.’s doctrine of nonconformity, when seen for what it is, shows up as highly positive rather than negative in its total impress.

Also, this consideration explains why having something “as though not” can be as effective as actually having it not. In many cases the thing is not evil in itself but only in the allegiance it attracts; thus to hold it “as though not,” as a thing of no value, is effectually to depotentiate it as a threat to the God relationship. And for that matter one easily can love the world even while possessing few if any things of the world; “as though not” truly may he a more radical solution than “having them not.” Thus “nonconformity to the world” is a much more accurate designation for S.K.’s position than would be “renunciation of the world.”

Admittedly, nonconformity is a much more demanding and a much less stable position than renunciation; it requires a fine balance that is anything but easy to maintain, as is the case with every dialectic. But, for instance, what qualities and things can be retained “as though not” and what must be renounced as absolute evils? To what extent can one “have” and continue to “have” these things without coming to them? At what point does honesty compel one actually to take leave of the thing in order to avoid its snares? Nonconformity, as all dialectic, can deteriorate so easily–and without it immediately becoming apparent what has happened. Thus, in the one direction, as S.K. contended was the case with his own church, everyone could and did “have” to his heart’s content as long as he gave lip service to the principle of having “as though not.” In the other direction, as was the case with nineteenth century Brethrenism, the demands of nonconformity could be met by the outward renunciation of a certain well-defined list of “things.” S.K. and the eighteenth century Brethren, we suggest, represented the dialectic in its true character of tension and balance.

S.K. did not give a great deal of attention to following out his conception of nonconformity as it regards the Christian’s relationship to the state. However, what he did say was very much in line with the sectarian Brethren position. In the first place, “Christianity has not wanted to hurl governments from the throne in order to set itself on the throne; in an external sense it has never striven for a place in the world, for it is not of this world.”33 Second, nonconformity in regard to government necessarily involves the issue of freedom of conscience. This need not, however, imply a pleading before, or bringing pressure upon, government in an attempt to win the concession, as though this freedom were in the hands of the state to give rather than being the innate possession of the individual. Twentieth century Brethrenism has tended to misinterpret its sectarian heritage at this point. But S.K. delineated the posture precisely when he said:

Ideally speaking it may be perfectly true that every man should be given freedom of conscience and freedom of belief, etc…. [But] the truth is that anyone who is so subjective that he only deliberates with God and with his own conscience, and is able to persevere, does not care a fig whether there are laws or regulations or not; to him it is only so much cobweb…. If it is really conscience, conscience alone, then your regulations be blowed–I should only laugh at them…. Ultimately no force can compel the spiritual, at the most it can oblige them to buy freedom at a higher price.34

This is exactly what it means to live above the law, submitting to it as an ordinance of God and a work becoming us to fulfill all righteousness–until a matter of conscience arises, a command of God–then “regulations he blowed,” the Christian takes freedom of conscience whether the state sees fit to grant it or not.

In this connection one of the almost infallible hallmarks for distinguishing the sectarian view from the churchly is the interpretation of the Gospel incident in which the Pharisees asked Jesus about the tribute money. S.K. diverged radically from the Lutheran conception of the two realms and stated the sectarian understanding as well as it has ever been stated:

Then give to the Emperor what belongs to the Emperor, and to God what is God’s.’ Infinite indifference! Whether the Emperor be called Herod or Shalmanezer, whether he be Roman or Japanese, is to Him the most indifferent of all things. But, on the other hand–the infinite yawning difference which He posits between God and the Emperor: ‘Give unto God what is God’s!’ For they with worldly wisdom would make it a question of religion, of duty to God, whether it was lawful to pay tribute to the Emperor. Worldliness is so eager to embellish itself as godliness, and in this case God and the Emperor are blended together in the question, as if these two had obviously and directly something to do with each other, as if perhaps they were rivals one of the other, and as if God were a sort of emperor–that is to say, the question takes God in vain and secularizes Him. But Christ draws the distinction.35

Alongside the state, of course, stands the established church. S.K.’s position toward it forms the theme of a later chapter, but there is an interrelationship with his doctrine of nonconformity which can better be noted here. In the first place he was critical of the church for failing to promulgate nonconformity.36 But in the second place, and much more fundamental, the very constitution of an established church makes impossible any real concept of nonconformity to the world, for “if every baptized person is a Christian and baptized Christendom is pure Christianity, then the world does not exist at all in a Christian country.”37 The logic is unimpeachable; where the churchly ideology is followed consistendy there is simply no way to define “the world,” let alone produce an effective doctrine of nonconformity to it.

The interpretation of S.K. as a humanist, a man of the world, cannot be sustained; there is, however, a charge often leveled against him from the opposite quarter which also demands consideration–this the attribution to him of monastic asceticism. The problem is well posited in a statement by H. Richard Niebuhr, made in the course of his giving examples the “Christ against culture” ideology: “Monastic characteristics reappear in Protestant sectarians; and a Lutheran Kierkegaard attacks the Christendom of post-Reformation culture with the same intransigence that marks a Wiclif’s thrust against medieval social faith.38

We, of course, concur heartily in this alignment of S.K. With the Protestant sectaries; we object just as heartily to the identification of S.K. and the sectaries with monasticism. Niebuhr’s suggestion is much more adequate than calling S.K. a Christian humanist; and even his phrase “monastic characteristics” might be acceptable enough, if he would be quick to allow the very basic distinctions between monasticism and the Kierkegaard-sectarian position. That difference amounts to our earlier distinction between “renunciation of the world” and “nonconformity to the world”: renunciation implies a leave-taking from all possible uses of the world; nonconformity, rather, a change of attitude toward, or evaluation of, the world. The difference is a very important one.

In the first place, nonconformity is in no way conceived as an act of merit or a work of supererogation. This aspect of Catholic monasticism simply was not in the thought of S.K. or the Brethren. In the second place, nonconformity is not asceticism in the customary sense of the word. There are no implications of dualism, of an evil (or at least, lower) realm encompassing physical reality, the body with its earthly needs and desires, which is then set over against the higher realm of the spirit. There are no suggestions about chastising the body for the good of the soul, about valuing punishment and deprivation for their own sakes, about giving up the comforts of life as a sacrifice to God. Nonconformity is not conceived as a sacrifice at all–any more than it is a “sacrifice” for a swimmer to shed his clothing before going in the water. He is merely doing what he can to make possible and to enhance the enjoyment of what he wants to do.

Thus, in the third place, the most significant distinction is that the nonconformist, even while struggling to he “not of” the world, is equally determined to remain “in” the world. Although completely opposed to adopting the world’s standard of values, S.K. did not so much as imply any leaving of the world. Certainly he did not renounce the world of other people, advocating any lessening of the responsibility to love, serve, share, and live with them–and in a chapter to come we will see that he made this a positive duty. Neither did he renounce man’s life in the natural institutions of society: family, business, community, state, or church. He made it clear that none of these dare be organized or valued so as to compete with one’s unconditional allegiance to God, but he did not say that any and every participation in these institutions constitutes illegitimate evaluation.39

Kierkegaard, both through the pseudonyms and in his own name, was explicit in discounting monasticism for its tendency to desert the world.40 As we have noted he even brought this criticism against the Moravians, whom he otherwise credited with the purest Christianity he had seen. [See S.K.’s own words quoted above]. He was, however, adamantly against the way in which the church strove to justify its worldliness by making invidious comparisons with these:

And [Christ] remained in the world, He did not retire from the world, but He remained there to suffer. This is not quite the same thing as when in our age preachers inveigh against a certain sort of piety… which seeks a remote hiding-place, far from the world’s noise and its distractions and its dangers, in order if possible in profound quiet to serve God alone…. Nowadays we do differently and better, we pious people, we remain in the world–and make a career in the world, shine in society, make ostentation of worldliness just like the Pattern, who did not retire cravenly from the world! … No, it certainly is not the highest thing to seek a remote hiding-place where it might be possible to serve God alone; it is not the highest thing, as we can perceive in the Pattern; but even though it is not the highest (and really what business is it of ours that this other thing is not the highest?), it is nevertheless possible that not a single one of us in this coddled and secularized generation is capable of doing it.42

So S.K.’s position is equally distinguishable from churchly, humanistic world conformity on the one hand and monastic, ascetic world renunciation on the other; it would seem to be at one with the nonconformity of classic Protestant sectarianism.

The evidence is that the eighteenth century Brethren shared S.K.’s ideal and approximated it in practice. True, the nineteenth century Brethren did retreat to the “cloister” alternative, moving to the sequestered communities of the frontier to form what amounted to cultural and religious enclaves, although even this is not to imply that they thereby took up the total pattern of Catholic monasticism. But there is little indication that their eighteenth century predecessors had sought out seclusion. Admittedly they had fled Europe, although that was a case of persecution as much as forcing them out; and in America their rural situation and the language barrier did contrive to make them somewhat isolated. But if the examples of the Germantown leaders can be taken as a indication of their ideology, then the careers of men like Mack Junior and particularly the publisher Sauer Junior are evidence enough that these Dunkers had no intention of deserting the world.

“In the world but not of the world”–and the bond which most strongly ties the Christian into the world is the command to love. The positive explication of this theme will be the work of a succeeding chapter, but at one point S.K. stated the relationship so concisely that his words can be used both to sum up the discussion of nonconformity and to point ahead to its positive counterpart:

[The Apostles] had the frightful experience that love is not loved, that it is hated, that it is mocked, that it is spat upon, that it is crucified, in this world…. So surely, they swore eternal enmity to this unloving world? Ah, yes, in a certain sense, but in another aspect, no, no; in their love for God, in order that they might abide in love, they banded themselves, so to speak, together with God to love this unlovngg world…. And so the Apostles resolved, in likeness with the Pattern, to love, to suffer, to be sacrificed, for the sake of saving the unloving world. And this is love.”43

In Dru’s and in Rohde’s selections from Kierkegaard’s journals, the number identifies an entry rather than a page; the date following is that of the particular entry.

1. Works of Love, 84.

2. Smith Journals, 11:2:A:113 (1854).

3. “Lifted Up On High …” (Part III, Reflection 7) in Training in Christianity, 218.

4. Quoted in Brumbaugh, op.cit., 243-45.

5. Mack Senior, Rights and Ordinances, in Durnbaugh, Origins, 367-68.

6. John Price (d. ca.1722), Geistliche und Andachtige Lieder [bound as an appendix to Der Wunderbahre Bussfertige Beichvatte] (Germantown: Sauer Press, 1753), Hymn I, Stanzas 4, 6.

7. Michael Frantz, op.cit., Stanzas 170, 280-81, 315.

8. Sauer Junior (presumably), “Eines Pilgers Gedanken vom Rechten,” in Der Hoch-Deutsch Americanische Calendar for 1767 (German-town: Sauer Press, 1767), 19-20 [my trans.–V.E.].

9. Mack Junior, a poem “God Alone is Good,” in Heckman, op.cit., 52-53, stanzas 5-6 (trans. amended–V.E.]

10. Jacob Stoll, op.cit., 189 [my trans.–V.E.]; cf., 107.

11. Discourse III on “What Is To Be Learnt from the Lilies …” in The Gospel of Suffering, 227.

12. Point of View, 82.

13. Note, for example, the place given to S.K. in Geddes MacGregor’s plea for Christian humanism, The Hemlock and the Cross (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1963).

14. Walter Lowrie, in the translator’s Appendix to S.K.’s Repetition, 208-9.

15. This Pauline concept is found in 1 Cor. 7:29-31: “I mean, brothers and sisters, the appointed time has grown short; from now on, let even those who have wives be as though they had none, and those who mourn as though they were not mourning, and those who rejoice as though they were not rejoicing, and those who buy as though they had no possessions, and those who deal with the world as though they had no dealings with it. For the present form of this world is passing away.”

16. Point of View, 87.

17. “He Is Believed On in the World” (Part III, Discourse 7) in Christian Discourses, 245-46.

18. “Courage Enables the Sufferer To Overcome the World …” (Discourse VII) in The Gospel of Suffering, 157. Cf. Discourse II on “What Is To Be Learnt from the Lilies” in The Gospel of Suffering, 212.

19. Point of View, 31ff., 39ff.

20. Ibid., 96.

21. Smith Journals, 11:1:A:55 (1854).

22. Dru Journals, 1288 1853).

23. Either/Or, 1:147.

24. Training in Christianity, 113-14.

25. Works of Love, 70.

26. 26 Ibid, 127.

27. Rohde Journals, 232 (1849).

28. Works of Love, 63.

29. Ibid., 243.

30. “To Win One’s Soul in Patience” (Discourse IV) in Edifying Discourses, 1:76. Cf. Smith Journals, 11:1:A:16 (1854).

31. Dru Journals, 614 (1846).

32. Discourse III on “What Is To Be Learnt from the Lilies … ” in The Gospel of Suffering, 228-33.

33. Works of Love, 137.

34. Dru Journals, 1155 (1850).

35. “Lifted Up On High …” (Part III, Discourse 3) in Training in Christianity, 169-70.

36. Works of Love, 62.

37. Ibid., 124.

38. H. Richard Niebuhr, Christ and Culture, 65.

39. We are compelled to recognize that at the very close of S.K.’s life, at scattered points in his private journals and in the periodicals that constitute the Attack, there appears a new note, or rather the hint of a new and frightening note. This material is not at all typical of, or even reconcilable with, the rest of his thought, but here appear signs of misanthropy, asceticism, and a masochistic desire for suffering. These notices appear so late and are so few that it is impossible to say what they signify, whether transitory lapses or the beginning of a tragic deterioration. In either case they hardly can be taken into account as part of the essential witness of Kierkegaard.

40. Stages of Life’s Way, 169-70; Postscript, 366; and “Christ as Example …” (Discourse II) in Judge For Yourselves!, 185.

42. “Christ as Example …” (Discourse II) in Judging for Yourselves!,. 179. Cf. Smith Journals, 11:1:A:263 (1854).

43. “It Is the Spirit that Giveth Life” (Discourse III) in For Self Examination, 103-4.

b. Oath-Swearing

We hold the Holy Scriptures in high honor.

When e.g. an oath is to be particularly solemn

we swear by laying the hand upon the Holy Scripture

which forbids swearing.1

S.K. and the Brethren were in agreement on some specific items of nonconformity which, although in one sense rather minor, or at least subsidiary, are striking enough in their coincidence to he worthy of notice. One such regards the swear-of legal oaths.

From the beginning the Brethren had understood the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5:33-37) as forbidding oath-swearing, and Brethren nonconformity in this matter is attested as early as Mack Senior’s Rights and Ordinances.2

Further attestation is found in Michael Frantz3 and in Sauer Junior, whose persecution during the Revolutionary War was brought on, at least in part, by his refusal to swear the oath of allegiance required by the new government.4 The church’s position was stated officially in an Annual Meeting minute of 1785: “And as to the swearing of oaths, we believe the word of Christ, that in all things which we are to testify, we shall testify what is yea, or what is true with yea, and what is nay, or not true with nay; for whatever is more than these cometh of evil.”5

S.K. did not give major attention to the matter of oath-swearing–as he hardly would have had occasion to do–and it is impossible to say whether he would have gone as far as the Brethren in actually refusing to take an oath. However, his passing references indicate that he viewed the problem as did the Brethren, and in fact did his viewing from the same perspective, a literal application of the Sermon on the Mount. In addition to the aside quoted as our headnote, S.K. elsewhere made the same point in another aside, saying that it is a contradiction to make “a man swear by laying his hand upon the New Testament, where it is written, Thou shalt not swear.”6

These statements from S.K.’s religious phase align him with the Brethren in their reading of the New Testament, but just as significant, and even more interesting, are the earlier sentiments of the nonreligious pseudonym Climacus. Again merely in passing, as illustrative of another point (but for that very reason quite revealing), Climacus said: “But when a man has indulged in oaths for a long time, he returns at last to simple utterance, because all swearing is self-nugatory.”7 And one hundred pages later Climacus returned to give the theme a more extended, and now self-conscious, treatment:

Only over-precipitate people, clouds without water and storm-driven mists, are quick to take an oath; because the fact is that they are unable to keep it, and therefore must perpetually be taking it. I, for my part, am of the opinion that ‘never to forget this impression,’ is something quite different from saying once in a solemn moment: ‘I will never forget it.’ The first is inwardness, the second is perhaps only a momentary inwardness…. Flighty and easily excitable souls are more prone to nothing than to the taking of a sacred promise, because the inner weakness needs the strong stimulus of the moment. To administer a sacred pledge to such a person is a very dubious thing.8

As in the previous statements S.K. related oath-swearing to a sectarian view of scriptural obedience, he here relates it to a sectarian view of inwardness.

The evidence is not extensive, but the very fact that S.K. identified himself even this far with a specific belief that is almost uniquely that of classic Protestant sectarianism–this fact is of some significance.

1. “To Become Sober” (Discourse I) in Judge For Yourselves!, 128.

2. Mack Senior, Rights and Ordinances, in Durnbaugh, Origins, 376.

3. Michael Frantz, op.cit., stanzas 367ff.

4. Sauer Junior, the account of his persecution, quoted in Brumbaugh, op.cit., 415ff.

5. Minutes of the Annual Meetings of the Church of the Brethren, 1778-1909, hereafter referred to as Annual Meeting Minutes (Elgin, Ill.: Brethren Puhlishing House, 1909), minutes of 1785, art. I, p. 20.

6. Attack upon “Christendom,” 130. Cf. For Self Examination, 36-37.

7. Postscript, 113.

8. Ibid., 214-15.

c. Celibacy

That a woman [the woman who

was a sinner (Luke 7:36-50)]

is presented as a teacher, as a pattern of piety,

can astonish no one who knows

that piety or godliness

is in its very nature a womanly quality.1

Woman might be called “joie de vivre.”

There is certainly a joie de vivre in man;

but fundamentally he is formed

to be spiritual and if he were alone

and left to himself he would not… know how

to set about it, and would never really get as far as beginning.

But then the joie de vivre,which is indefinite and vague

within him, appears outside him in another form,

in the form of woman who is joie de vivre;

and so the joy of life awakens.2

It is not often that one can catch S.K. in an out-and-out contradiction, but here is a bad one. Woman is either a symbol of godliness that can lead a man into spirituality, or else she is a symbol of joie de vivre that can lead a man into worldliness-SIC. was not quite sure which. Eighteenth century Brethren thought displayed something of the same, or at least a related, ambiguity. Apparently S.K. and the Brethren finally came out at opposite conclusions, S.K. supporting Christian celibacy, the Brethren Christian marriage. But the significance of the comparison lies not in the divergence of their conclusions but in the agreement of their confusions. The Kierkegaardian-Brethren ambiguity must be seen in contrast to the Roman Catholic certainty that celibacy is required for the higher righteousness of “spiritual Christians” and the churchly-Protestant certainty that celibacy is as much as prohibited for normal Christian spirituality.

We will advocate the position that S.K. concluded his life as a supporter of universal Christian celibacy, but we also will strongly resist the interpretation that would make S.K. such from the outset and then draw implications regarding his solitariness and world renunciation. Any such reading of the Regina incident cannot be reconciled with certain plain and forthright statements by S.K. For example:

I do not maintain, and have never maintained that I did not marry because it was supposed to be contrary to Christianity, as though my being unmarried were a form of Christian perfection. Oh, far from it…. My greatest pleasure would have been to have married the girl to whom I was engaged…. [But] I remained unmarried, and so had the opportunity of thinking over what Christianity really meant by praising the unmarried state.3

There is nothing in S.K. to indicate anything but that this asseveration was entirely honest and was his honest understanding throughout his life. Even when, in 1854-1855, at the very end of his career, S.K. seemingly took a view that would make celibacy a Christian requirement, the situation was not changed: S.K. did not arrive at this position until thirteen years after he had broken with Regina; he never mentioned Regina in the process of presenting this final opinion; and if there was any real connection between the breaking of the engagement in 1841 and the advocating of Christian celibacy in 1854, it is by no means clear what the nature or significance of that connection might be. In short, the Regina incident, far from being the key to Kierkegaard’s witness, is of very questionable help in understanding S.K.’s religious views even of marriage, let alone the religious life as a whole. His relationship to Regina involved so many purely personal factors that it hardly can be used as a source from which to derive a clear picture of his ideology.

We have called S.K.’s thoughts on marriage “confused”; this term is somewhat misleading if not unjust. S.K.’s was certainly a changing view but not by that token a chaotic one; if his statements are traced period by period a quite consistent pattern appears.

Phase I: The Regina Incident and S.K.’s Cogitations Regarding It

This, as we have suggested, was predominantly a personal matter from which S.K. did not (and explicitly refused to) generalize concerning a Christian doctrine of celibacy per se. This phase is of little help to our study, although, as we shall see, it does lend some support to Phase IV.

Phase II: The Aesthetic Pseudonyms (In Particular, those of Either/Or I and of the Banquet in Stages on Life’s Way)

Here are both confused and inadequate views of marriage. Among these pseudonyms are “woman-lovers,” analysts who approve of love, “woman-haters,” and analysts who approve misogyny; and ultimately all of their views-those of the lovers as well as the haters-show up as inadequate and false. But this disorder ought not be laid to S.K.’s charge, for it was precisely his design to demonstrate that the aesthetic view is by nature confused and partial. Far from attempting to elucidate his own position, S.K. was deliberately using pseudonyms in order to assert that aesthetic analyses are futile.

Thus one cannot, as some would do, read, for example, the speeches of the banquet as an indication of S.K.’s own hatred of women-particularly when S.K. himself explicitly stated:

The five speeches, … which are all of them caricatures of the most holy, are written with the idea of bringing an essential, but nevertheless false, light to bear upon woman.4

It is a very uncertain procedure to try to divine S.K.’s true opinion of women out of these pseudonyms; they were never intended to incorporate his view, and they present no consistent picture within themselves. The only positive contribution this material can make to our quest is to say, “The answer is not with me,” the truth about women and marriage lies not in the aesthetic sphere.

Phase III: The Ethical Pseudonym (In Particular, Judge William, as He Appears Both in Either/Or II and Stages

We have rejected Phases I and II as being all but useless in leading us to S.K.’s true religious position regarding marriage; Phase III is much more helpful. Those commentators who tend to make Phases I and II normative and thus portray S.K. simply as a misogynist must overlook the fact that also within the writings of Søren Kierkegaard are to be found some of the most impressive pictures of conjugal happiness and some of the most profound analyses of the marriage relationship to occur anywhere. These commentators ignore the obvious fact that the banquet passage consciously is structured so that the mere appearance of the concrete and actual love relationship of Judge William and his wife immediately gives the lie to all the high-flown philosophizing of the banqueters.

Phase III presents as exalted a view of marriage as can be conceived, always from the mouth of Judge William, the ethicist, who makes such statements as these:

What I am through her, that she is through me, and we are neither of us anything by ourselves but only in union. To her I am a man, for only a married man is a genuine man.5

In paganism there was a god for love but none for marriage; in Christianity there is, if I may venture to say so, a God for marriage and none for love.6

Marriage I regard as the highest telos of the individual human existence, it is so much the highest that the man who goes without it cancels with one stroke the whole of earthly life and retains only eternity and spiritual interests.7

I do not say that marriage is the highest, I know a higher; but woe to him who would skip over marriage without justification…. [Any exception] must occur in the direction of the religious, in the direction of spirit, in such a way that being spirit makes one forget that one is also man, not spirit alone like God.8

A very obvious difference between Phase III and Phase II is that Phase III has arrived at one consistent viewpoint. Likewise, this viewpoint displays insights that are much more profound, positive, and religious than those of even the greatest “lovers” of Phase II. Judge William is still a pseudonym (and this dare not be forgotten); Phase III does not present us with S.K.’s direct and final word.

A consideration of the general relationship between S.K.’s “stages of existence” will help elucidate the relationship between the specific “phases” that concern us here. S.K. held that a decisive “either/or” falls between the aesthetic and the ethical stages but that the progression from the ethical to the religious is much more gradual and continuous. Thus one must choose between Phase II and Phase III, between the banqueters on the one hand, Judge William and wife on the other. S.K. made this dichotomy very clear. It does not follow, however, that the same sort of choice is to be posited between the ethicist Judge William on the one hand and the religious view of S.K. himself on the other. Here the relationship we would expect (and which will prove to be the case) is that Judge William represents a truth which is nevertheless a partial truth; religious-Christian considerations will not cancel or supersede Judge William’s position but definitely will supplement and modify it. It is highly significant to note that, in Judge William’s third and fourth statements quoted above, there are explicit hints of other considerations yet to come.

Phase IV: The Direct Religious Writings up until the Attack

In this phase are present two different conceptions which on first thought may seem contradictory but probably are not. In the first place there is the continuation of the Judge William line in which woman is praised as a spiritual helpmeet and example. The first of our two epigraphs is characteristic of the long passage of which it is a pan–this from a discourse of 1850. Another such passage occurs in For Self-Examination (1851).9 The comparative lateness of both these dates is significant.

But alongside this strain appears another, a specifically Christian note. One example will make S.K.’s thought plain:

It is quite certain and true that Christianity is suspicious of marriage, and desires that along with the many married servants it has, it might also have an unmarried person, a single man; for Christianity knows very well that with woman and love all this weakliness and love of coddling arises in a man, and that insofar as the husband himself does not bethink himself of it, the wife ordinarily pleads it with ingenuous candor whtch is exceedingly dangerous for the husband, especially for one who is required in the strictest to serve Christianity.”10

There would not seem to be any necessary opposition between the affirmation

- that woman has an instinct for genuine religiousness which can be of inspiration to a man, and

- that family life inevitably involves a man in worldly concerns that make it difficult for him to act completely and solely for God.

In fact the recognition of both truths might well lead to S.K.’s customary dialectical treatment except that it proves somewhat awkward to apply the method to marriage. One hardly can be both married and not married at the same time; neither does rapid oscillation between the two quite achieve the purpose; and even being married “as though not” is somewhat impractical, although this is precisely what Paul did advocate in 1 Cor. 7:29.

The position S.K. actually took would seem to be as near to dialectical as is feasible. His was a doctrine of “vocational celibacy.” Ethically understood, marriage is a moral imperative that applies universally (Phase III is not rejected). Christianly understood, marriage is proper and good, the “normal” mode. However, the cause of true religion also needs (not, “the law of the church requires”) the contribution that only a celibate can make. God calls a few Christians, the “exceptions,” to a specialized service that needs the specialized qualifications found only in a celibate.

Though there may be some points of contact, this view differs greatly from that of Roman Catholicism. With S.K. the call is entirely a private matter between den Enkelte and God and is so exceptional a case that no generalizations can be drawn at all. Den Enkelte must bear the full responsibility for having presumed “a teleological suspension of the ethical” (to use the language of Fear and Trembling), being willing to pay the price and risk the misunderstanding that such exceptions incur. This is a far different thing than a formal requirement of the church applied wholesale to an entire class of men as a prerequisite for achieving an elevated spiritual status. No merit accrues to the Kierkegaardian celibate; he has done no more than the married Christian has done, because each has sought simply to find the will of God for his particular life. But as God may call one man to sacrifice his fortune to the cause, another his social status, another perhaps his life, so may he call still another to sacrifice his marriage. And S.K. clearly, explicitly, and consistently interpreted his break with Regina precisely in this frame of reference; he always thought of himself as “the exception” and did his utmost to prevent his action from being generalized into a rule.

Up to this point, apart from the complicating factors of Phase I (i.e. his personal actions in regard to Regina), S.K.’s thought about Christian celibacy has followed the pattern that almost could be predicted; the development is of a piece with the rest of his religious thought. And Phase IV, which falls where we would expect to find the authentic Kierkegaardian witness, we take as being just that. This position is not typically churchly-Protestant; the fact that it so much as shows concern over the possibility of a Christian celibacy is a distinction, a distinction which, we intend to show, actually is sectarian in character.

Phase V: During the Attack (1854-1855)

Contrary to S.K.’s usual pattern, during the closing months of his life, coincident with his attack upon Christendom, he seems to have drifted past sectarianism and into a view of marriage that can be adjudged only as “cultic.” In several places in the periodicals that made up the Attack and more particularly in the unpublished journals of that period, S.K. condemned marriage and childbearing per se, making such statements as: