Kierkegaard and Radical Discipleship:

A New Perspective

by Vernard Eller

Table of Contents

To my two sons, Sander Mack Eller and Enten Eller.

Part I: THE PERSPECTIVE

- The Central Nerve

- Where Is True Christianity to Be Found?

- Classic Protestant Sectarianism: In Which a Church Is Not a “Church”

- A Sect Called The Dunkers

Part II: THE DUNKERS AND THE DANE

- The Decisive Christian Category

- The Character of Den Enkelte

- The Problem of Sociality

- The World Well Lost

- The World Well Loved

- The Church Well Lost

- The Church Well Loved

- Christ as Savior and Pattern

- The Christian’s Book

Part III: THE OPENING CONCLUSION

Preface

This book comes as the product of a rather long development. It all began, I guess, when, as a junior at La Verne College, I first discovered Kierkegaard–March 22, 1948, the check-out card in the library book says. The circumstances, I feel, were propitious for helping me become one whom S.K. hopefully might address as “my reader.” I was wandering through the stacks of the college library when a bright blue volume carrying on its spine the glittering gold letters KIERKEGAARD caught my eye; it was Bretall’s anthology from Princeton University Press. Curious as to who or what such a label could represent, I took down the book, flipped through its pages (starting at the back), immediately hit some of the short-and-sharp entries of the Attack upon “Christendom,”

and was captured.

I checked out the book six times in as many months and then began buying Kierkegaard on my own. Thus I had read a good deal of S.K. before reading any books about him; had read S.K. before I even heard of existentialism, dialectical theology, and such; had listened to S.K. speak before I listened to anyone tell me what he said; had read deeply in the religious works before going to the pseudonymous ones-and all this I consider providential. It was almost seven years later that, as a student at Bethany Biblical Seminary (Church of the Brethren) in Chicago, I was taking a course in the history of Christian doctrine concurrently with one in philosophical ethics. I got permission from the respective professors to submit in the two classes one double-length paper exploring the affinity between Kierkegaard and Pietism.

Each of the teachers decided to keep the copy I gave him (my only two copies). Floyd E. Mallott, the church history professor–to whom I owe much of my understanding of Brethren history–had me read part of the paper in class and encouraged me to pursue this line of investigation. Donovan Smucker, the ethics professor, wanted to submit the manuscript to The Mennonite Quarterly Review; but when it came time to do so, neither professor could find his copy. That primordial “J Document” was lost for several years, and only half of it has been located to this day–not that it is any great loss. But dating from that time was my determination to do a doctoral dissertation on Kierkegaard and sectarianism.

I chose my school, my field, and my department–all with an eye to making this study. At the Pacific School of Religion (Berkeley, California) I did my work in historical theology under John von Rohr, a man who became mentor, friend, and colleague in an exceedingly helpful way. I also had courses- and much more than just courses-from Robert E. Fitch and Hugh Vernon White. Although Dr. White retired before my dissertation was well underway, he continued to give me help and counsel on it.

By this time (1958) I was teaching at La Verne College, but my topic, outline, and prospectus were accepted without difficulty. A grant from the Swenson Kierkegaard Fellowship Committee helped finance some of my research, and appreciated assists from my college administration kept the project moving. Things went smoothly until it came to producing a draft that would satisfy my doctoral advisors. Then, at one point, just three brief months before deadline, I seriously proposed to Dr. von Rohr that I drop the Kierkegaard half of my study and write a brief and innocuous discourse on the Brethren. He responded with a direct command, which is all that kept me at the task. The finished dissertation was accepted without dissent.

My doctorate behind me (1964), I reworked the manuscript and started the search for a publisher. It was at this point that Franklin H. Littell, authority on Protestant sectarianism and then professor of church history at Chicago Theological Seminary, read the volume and for no reason other than the benevolence of his good heart took the initiative in contacting prospects. Nevertheless, the hook seemed doomed to remain forever a manuscript when the editors at Charles Scribner’s Sons for no reason other than the benevolence of their good hearts–took it upon themselves to recommend it to Princeton University Press. And at Princeton it has been the benevolent heart and kindly hands of managing editor Eve Hanle that have brought to completion this work of ten, thirteen, almost twenty years.

The greatest satisfaction to come out of this long-drawn process is the friends made along the way. To each of the persons named above I proffer heartfelt thanks-as I do to an even greater number who must go unnamed: my wife, parents, family, and friends; my colleagues of the faculty and ad- ministration here at La Verne College; my fellow scholars within the Church of the Brethren; and the librarians without whose help few books would get written and few, indeed, read. May the contribution of this book prove worthy the trust they all have put in me.

PART I: THE PERSPECTIVE

I. The Central Nerve

The central nerve of my work as an author

really lies in the fact that I was essentially religious

when I wrote Either/Or.1

Count it not presumption that this study sets itself to do for Søren Kierkegaard what Adolf Deissrnann did for the Apostle Paul. In the following excerpt from Deissmann’s classic work, read “Kierkegaard” for “Paul” and the words retain both their accuracy and relevancy:

[Scholarly research] has been most strongly influenced by interest in Paul, the theologian, and in the ‘theology’ of Paul…. But with this doctrinaire direction the study of Paul has gone further and further astray. It has placed one factor which is certainly not absent from Paul, but is in no way the historically characteristic, theological reflection, in the foreground, and has only too often undervalued the really characteristic traits of the man, the prophetic power of his religious experience, and the energy of his practical religious life…. Paul at his best belongs not to Theology, but to Religion…. The tent-maker of Tarsus ought not to be classed along with Origen, Thomas Aquinas and Schliermacher: his place is rather with the herdsman of Tekoa, and with Tersteegen, the ribbon-weaver of Mulsheim…. Paul is essentially first and foremost a hero of religion. The theological element in him is secondary. Naivete in him is stronger than reflection; mysticism stronger than dogmatism; Christ means more to him than Christology, God more than the doctrine of God. He is far more a man of prayer, a witness, a confessor and a prophet, than a learned exegete and close thinking scholastic. To show that this is so, is, I consider, the object of this sketch.2 And, concerning Kierkegaard, the object of this “sketch” is not far different.

Actually, although he nowhere stated the distinction quite as Deissmann did, S.K. wrote an entire book, plus a number of briefer essays,3 in the interest of subsuming his authorship under the religious category:

The contents of this little book affirm, then, what I truly am as an author, that I am and was a religious author, that the whole of my work as an author is related to Christianity, to the problem ‘of becoming a Christian.’ … I would beg of every one who has the cause of Christianity at heart-and I beg the more urgently the more seriously he takes it to heart that he make himself acquainted with this little book, not curiously, but devoutly, as one would read a religious work…. [The reader] will totally misunderstand me, [if] he does not understand the religious totality in my whole work as an author…. What I write here is for orientation. It is a public attestation; not a defense or an apology…. It goes without saying that I cannot explain my work as an author wholly, i.e, with the purely personal inwardness in which I possess the explanation of it. And this in part is because I cannot make public my God relationship.4 Clearly, S.K. was meaning to say that his writings cannot properly be understood, that he desired that they not be read, as the work of a philosopher, a psychologist, a social critic, an aesthete, or whatever. The criteria of these disciplines are not appropriate to his orientation.

Also, it is evident that he would have included theologian among the things he was not. “Theological” simply will not do as a synonym for “religious” in S.K.’s context. An authorship which centered on “becoming a Christian” (as against “defining the Christian faith”), which was to be read “devoutly,” and which integrally involved the author’s personal God-relationship–this is not “theology” in the usual sense of the term. Rather, S.K.’s opinion of theology was expressed in such statements as:

To me the theological world is like the road along the coast on a Sunday afternoon during the races-they storm past one another, shouting and yelling, laugh and make fools of each other, drive their horses to death, upset each other, and are run over, and when at last they arrive, covered with dust and out of breath-they look at each other-and go home.5

From a Christian point of view a dogmatic system is an article of luxury; in fair weather, when one can guarantee that at least an average of the population are Christians, there might be time for such a thing-but when was that ever the case? And in stormy weather the systematic is deprecated as an evil; at such times everything theological must be edifying. 6 As we shall discover, S.K.’s concern was over the intellectualistic bias he found in theologizing; he was convinced that Christianity must be life-centered and so resisted passionately any tendencies that might make it thought centered [see below].

However, Point of View notwithstanding, it must be confessed that Kierkegaard scholarship generally has proceeded to treat S.K. precisely contrary to his wishes and his own self-understanding, reading him as a philosopher, theologian, or whatever.

Recently, however, prominent scholars are showing interest in correcting the situation. For example, Perry LeFevre maintains that S.K. should be seen essentially “as a religious man struggling for his own soul” and “sympathetically understood in the context of his own pilgrim’s progress.” 8 Paul Holmer makes an extended plea “for a kind of understanding that fits the [Kierkegaardian] literature,” 9 and is extremely critical of a fellow scholar for expounding S.K. as though he were a theologian.10 And Niels Thulstrup becomes quite vocal against those thinkers and schools that attempt to analyze S.K.’s ideas from perspectives that are “totally incommensurable with them.”11 This growing trend has the effect of taking S.K. out of the mainstream of Christian philosophic-theological development but does not, to this point, suggest where he should be put. Does S.K. represent a “sport” in Christian thought, or is there a totally religious yet nontheological (antiintellectual) tradition to which he should be related? There have been forthcoming some scattered hints that may point toward an answer.

Niels Thulstrup (a Danish pastor and highly competent Kierkegaard scholar), as the alternative to his criticism noted above, proposes that “with respect to content there is in fact only one yardstick of values for Kierkegaard, namely, the authority he himself appealed to and quoted: the Bible, and in the Bible particularly the New Testament”12

William Barrett (a philosophy professor specializing in existentialism) anchors the line of traditional Christian philosophy-theology in what he calls “Hellenism” and the Kierkegaard-existential line in “Hebraism.” He sees the latter as predominant in New Testament Christianity, as being represented to some degree in Tertullian and even more so in Augustine. However, he specifies that Augustine only opened the door but did not go inside, in that he also retained a strong orientation toward the “rationalist” strain. Barrett denies that Thomas Aquinas and the other medieval philosophers showed any significant relation to existential thought. At this point he abandons the tracing of the historical development and moves directly to the nineteenth century and Kierkegaard.13

L. Harold DeWolf (a professor of theology who is not particularly sympathetic to existential irrationalism) notes the presence of this strain in such contemporary theologians as Barth, Brunner, and Reinhold Niebuhr and ascribes the influence to S.K. Then, in tracing the antecedents of S.K.’s irrationalism, he starts with the New Testament, mentions Tatian, stresses Tertullian, points to aspects of irrationalism within Luther and Calvin–and thus to S.K.14

Three philosophy professors–William Earl; James M. Edie, and John Wild–more recently have collaborated on a work, Christianity and Existentialism. Although the book is a symposium, the men coordinated their ideas and thus present an integrated viewpoint. The basic frame of reference is as follows:

What seems certain is that if we now observe the history of Christianity from the viewpoint of Kierkegaard’s conception of faith as action rather than knowledge, we find that it is not something new but that it has been one of the two constants in Christian life from the beginning. There has always been a strain of what can be called Christian ‘irrationalism’ (which is not always to be understood as an ‘anti-rationalism’) opposed to the strain of Christian ‘rationalism’ in the Christian experience of the world. There have always been ‘philosophers of the absurd’ to challenge the Church theologians in their conception of faith as knowledge and theology as science.15

The authors do not proceed to trace this strain of Christian “irrationalism” consistently in any detail, but by putting scattered references together it comes to this: The line is rooted in the Bible. It achieved its clearest expression in Tertullian and the Punic fathers in contrast to the other church fathers whose faith was becoming strongly Hellenized.16

Augustine stands in the train of these Punic fathers but also shows strong aspects of Christian rationalism as well. Thomism belongs wholly in the rationalist line, “but with Scotus, then Ockham and the Franciscan spiritualist movement, we find a gradual change of climate.” This change “prepared for Luther’s revolt and the new sense it gave, temporarily, to the Pauline ‘primacy of faith.’” But very soon Protestantism itself became “official Churches with their own orthodox and scientific theologies.” Thus, “movements of protest appear in the form of the pietist movement in Germany, the puritan revolt in England, Pascal and the Jansenist heresy in France.”17

It is not our intent to endorse or defend any of the above analyses, particularly in their details, but to show that within the Kierkegaard scholarship of our day there is developing at least some agreement about the antecedents of S.K.’s “irrationalism” (antiintellectualism). There is also becoming apparent a second tendency, this one seemingly not related to the first and not focusing particularly on S.K.’s irrational aspect. The suggestion, first made by Emil Brunner and now gaining considerable support, is that S.K. was molded by and should be understood within the context of continental Pietism [see below]. We shall relate these two developments to each other in due course. Thus far our examination has been of tendencies which but recently have showed themselves within Kierkegaard studies. Now, however, let us put S.K. to one side for the moment and consider a completely independent and long-established school of thought within church historiography. The basic idea perhaps has never been given a more succinct and colorful statement than in the words of Leonhard Ragaz:

[There is] one great antinomy, which runs right through the whole history of Christianity, and is indeed even older than Christianity itself. I would like to describe this contrast as that which exists between the quiescent and the progressive form of religion. In other words, it might be described as the difference between an aesthetic-ritualistic piety and an ethical-prophetic piety. Both streams may have taken their rise in the depths of the same mountain range, but they emerge from the mountains at different places, their waters are differently coloured, and they have a different taste. They arise … in the New Testament, but not at the same point; the one springs out of the thought of Paul and of John, the other out of the Synoptic Gospels.19

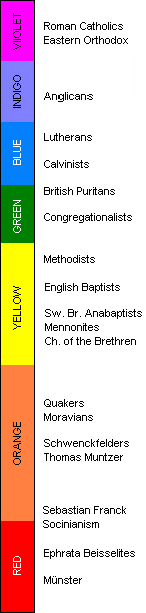

Our intention here, again, is not to commit ourselves to any of the particulars of the above analysis but only to the conception of two streams of differing color and taste. Although a great deal of ‘scholarship has recognized, or at least hinted at the presence of, these two streams, there never has been any consensus on how to describe or even name them. In the interests of keeping the subject as open as possible, we will use a very broad terminology, calling one the Established Tradition and the other the Radical Protest.

This bipartite analysis of Christian history seems first to have been proposed during the Reformation itself, by the leftwing spiritualist historian Sebastian Franck. His Chronica, Zeitbuch, und Geschichtbibel (1536), included a Ketzerchronik, i.e. a chronicle of the so-called heretics of Christian history (up to and including the Anabaptists of his own day), intended to demonstrate that there was at least as much if not more true Christianity represented in this stream as in the Established Tradition. Franck’s idea was picked up, developed, and introduced into modern historiography through the work of the Radical Pietist historian Gotifried Arnold.20 The stated theme of his Unparteiische Kirchen- und Ketzer-Historic was that “those who make heretics are the heretics proper, and those who are called heretics are the real God-fearing people.”21

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the treatment of this Established-Radical typology reached a climax. The crowning achievement was Troeltsch’s grand design of “church” and “sect,”22 although as the voluminous footnotes to his great book make clear, there were at the time a host of scholars engaged in this line of research–men such as Ragaz, Keller, Hegler, Ritschl, Göbel, and Weber.23 It is significant that although these scholars were agreed that there are two streams, they were not at all in accord as to their meaning and value. Opinion ranged from that of Ludwig Keller, who was zealous to maintain that the Radical Protest represented true Christianity and the Established Tradition a monstrous perversion, through Troeltsch himself, who endeavored to give an objective assessment of both, to Albrecht Ritschl, who was certain that the Radical strain was of the devil.

From more recent times have come two major treatments that deserve notice. Monsignor Ronald Knox, in his long and detailed study of the Radical line, is inevitably of Ritschl’s opinion, although obviously he does not follow him in denouncing the Protestant Radicals by use of the Ritschlian gambit that brands them as Catholics.24

But what may well be the most incisive analysis yet to appear is Emil Brunner’s The Christian Doctrine of the Church, Faith, and the Consummation.25 Brunner gives but little attention to the historical tracing of the streams, hut he discloses the basic ideology of the two with greater profundity than has been evident heretofore. During the Troeltschian period the focus had been preeminently sociological dealing with the outward aspects of church and sect in their relation to culture. Brunner includes this interest but goes on to show that the antinomy vitally affects almost every aspect of doctrine and experience. Indeed, as regards the understanding of “faith” in the two streams, he speaks to what is essentially the same distinction that the Kierkegaard scholars have made between “theology” and “religion,” “rationalism” and “irrationalism.”

At this point it will be instructive to note how Troeltsch, Knox, and Brunner, respectively, trace out the Radical line. First, Troeltsch and what he calls the “sects” (as against the “churches”): He specifically identifies primitive, New Testament Christianity as of the sect type.26 He mentions Montanism in connection with this line,27 but does not feel that the “church” development had progressed far enough to make the distinction clear until the time of the Donatist controversy or even the Gregorian reform.28 He recognizes that Augustine played a somewhat ambiguous role, displaying characteristics of both streams.29 The line then runs: Waldensians, Franciscans, Wyclif and the Lollards, the Hussites. Coming to the Reformation, he notes the ambiguity in Luther (not by that token in Lutheranism) and points out how many analysts, dating as far back as Luther’s Anabaptist contemporaries, had resolved this by identifying the beginnings of Luther’s reform with the Radical line and his later work with the Established.30 During the Protestant period, then, the line runs, roughly: Anabaptists, General Baptists, Pietism (which he somewhere calls “the second great expression of Protestant sectarianism”), Moravianism, Methodism.

Ronald Knox traces the line which he calls “enthusiasm” from the schismatics whom Paul disciplined in the church at Corinth, through Montanism (of which he says, “For us, Montanism means Tertullian”31 ), Donatism, Albigensianism, Catharism, Waldensianism, Anabaptism, Quakerism, Jansenism, Quietism, Moravianism, Methodism. His evaluation of the whole and the pans is negative. Brunner’s approach is somewhat different. He posits the New Testament Ekklesia as a norm, labels the growth of the “church” idea (the Established line) as “a disastrous misdevelopment,”32 and then traces what he calls “delaying factors in the development of the Ekklesia into the Church, and attempts to restore the Ekklesia.”33 This line runs: Montanism, Novatianism, Donatism. Brunner recognizes the ambiguity of Augustine and even compares it with that of Luther. 34 The line continues: Cluniac and Cistercian monastic reforms, Franciscanism, Waldensianism, the Anabaptist movement, and the modern Free Churches. Luther’s problem in trying to represent both streams at once is described explicitly.35

This review makes possible some general observations: There are many and reputable church historians who identify the parallel development of an Established Tradition and a Radical Protest running through Christian history. There is general agreement in identifying the course of the streams, even among those who differ greatly in defining and evaluating them. Also, rather clearly, the scholars who have been searching for the existential antecedents of Kierkegaard’s thought have hit upon one element (i.e. antiintellectualism) belonging to the Radical Protest described in church historiography. An obvious question follows: Does the totality of S.K.’s thought and witness fit the Radical-sectarian pattern in the way that his antiintellectualism seems to do? If this is a possibility, the logical point of contact and comparison, in view of the fact that S.K. was a Protestant, would be with the Protestant phase of the Radical line, or what we shall call Classic Protestant Sectarianism.

At the outset, then, to approach Kierkegaard from a religious orientation implies certain principles of interpretation:

- To grant S.K.’s premise that he was a totally religious author and conscientiously to interpret him according to his own instructions in Point of View.

- To understand that this move effectually takes him out of the churchly, Philosophic-theological perspective where he customarily has been considered and puts him into “a stream of a different color and taste”–a change of viewpoint which has fundamental implications regarding the understanding of S.K. And

- to demonstrate that S.K.’s religious witness on around a view of radical discipleship that was essentially one with that of Classic Protestant Sectarianism.

At the outset, then, to approach Kierkegaard from a religious orientation implies certain principles of interpretation:

First, as the work of a totally religious author, his writings–when taken as a whole, as an integrated and connected authorship–display a certain structure or pattern. His individual works cannot be fully understood apart from the context of this overall organization, S.K. explained what he had in mind:

The movement described by the authorship is this: from the poet (from aesthetics), from philosophy (from speculation), to the indication of the most central definition of what Christianity is–FROM the pseudonymous “Either/Or,” THROUGH “The Concluding Postscript” with my name as editor, TO the “Discourses at Communion on Fridays,” two of which were delivered in the Church of Our Lady. This movement was accomplished or described uno tenore, in one breath, if I may use this expression, so that the authorship, integrally regarded, is religious from first to last–a thing which everyone can see if he is willing to see, and therefore ought to see.’36

In a Christian sense simplicity is not the point of departure from which one goes on to become interesting, witty, profound, poet, philosopher, etc. No, the very contrary. Here is where one begins (with the interesting, etc.) and becomes simpler and simpler, attaining simplicity…. But since the aim of the movement is to attain simplicity, the communication must, sooner or later, end in direct communication.37

“Progressive revelation” is the key to Kierkegaard. To a lesser extent his authorship is a tracing of the revelation that came to him. To a much greater extent it is S.K. progressively disclosing his thought to the reader; his journals make it obvious that throughout the pseudonymous works (up to and including Postscript) the “edifying author” was himself far in advance of the ideas he wrote in his hooks, that he was deliberately holding back some vital aspects of his thought. The disclosure, then, is progressive not so much in that the course of the authorship is marked by the introduction of new and explicitly religious themes as by the fact that early themes, first presented in aesthetic or philosophic guise, are gradually revealed in their truly religious depth, grounding, and “simplicity:’ It is amazing how many of S.K.’s major motifs appear in one form or another in his very earliest works; and yet with none of these do we have the full picture until the concept has been followed through to its religious fulfillment in the later writings.

As S.K. insisted so strongly, the end (both finis and telos) of the entire development was the religious: “[What] requires no explanation at all is the last section, the purely religious work which of course establishes the point of view.”38

It follows, then, that S.K.’s later works should be made normative for understanding his earlier ones. This is not to say that a statement of late date always must take precedence over all earlier statements; it does not mean that Attack upon “Christendom” is necessarily S.K.’s final word. It does mean that the early, pseudonymous writings are to be read in the light of the later, religious work; that one gets a better picture of Kierkegaard and his message by standing at the close of the authorship looking backward rather than at the beginning looking forward.

Secondly, from this follows the rather important consideration that to expound his books in chronological order is not the best way to expound S.K.39 They had to be written in the order they were, partly because S.K.’s own education was involved, partly because he was attempting a grand experiment in maieutic pedagogy. That experiment was not a complete success, as S.K. himself came to see. His laborious and repeated efforts to “explain” the authorship (as represented by the documents collected in Point of View) were an attempt to obviate the misunderstanding which even then he saw arising. But considering the fact that we have the entire authorship accessible to us, plus S.K.’5 own explanations and warnings, it does seem rather unwise to lead people to the essential Kierkegaard by wending the tortuous length of the chronological labyrinth.

Third, closely related to the foregoing is the caution that S.K.’s pseudonyms be given the weight and significance he intended for them. He was himself particularly concerned on this score:

o in the pseudonymous works there is not a single word which is mine, I have no opinion about these works except as a third person, no knowledge of their meaning except as a reader, not the remotest private relation to them…. My wish, my prayer, is that, if it might occur to anyone to quote a particular saying from the books, he would do me the favor to cite the name of the respective pseudonymous author.40

S.K. regularly followed his own precept; in the journals and elsewhere he ascribed references from the pseudonymous works to the pseudonyms themselves.

He was clear about the purpose of the pseudonyms and their relation to his nonpseudonymous works:

But from the point of view of my whole activity as an author, integrally conceived, the aesthetic work is a deception, and herein is to be found the deeper significance of the use of pseudonyms…. What then does it mean, “to deceive”? It means that one does not begin directly with the matter one wants to communicate, but begins by accepting the other man’s illusion as good money. … Let us talk about aesthetics. The deception consists in the fact that one talks thus merely to get to the religious theme. But, on our assumption, the other man is under the illusion that the aesthetic is Christianity; for, he thinks, I am a Christian, and yet he is in aesthetic categories.41

It does not follow that S.K. personally would have rejected out of hand everything the pseudonyms said; their ideas are not so much false as they are partial and incomplete; missing is the religious source and background, the only setting in which they become an expression of S.K.’s full intention.

Regarding our use of the pseudonyms, then, two principles would seem to be in order:

- We should honor S.K.’s request that the pseudonymous works be cited under the names of their respective authors. This certainly can do no harm, and it will alert the reader to at least the possibility that, had S.K. been speaking under his own name, he might have put the thought within a different context or expressed it somewhat differently.

- When expounding Kierkegaard by using pseudonymous materials, we would do well to keep one eye, as it were, on the direct, religious works as a norm against which to supplement and correct the pseudonymous statements themselves. Often, of course, no modification will be called for; in some cases it definitely will.

Fourth, much more than most authors, particularly in his journals, S.K. went back to discuss and comment upon his own earlier writings. Such helps, of course, should be used for all the assistance they can provide.

Fifth, the very nature of S.K.’s religious orientation required that his writings be unsystematic; this lack of system–which every analyst is quick to observe–was not just a personal idiosyncrasy of the author hut one of his principles of conscience. Thus every attempt to expound S.K.’s thought by forcing it into a systematic mold is bound seriously to distort it. As Louis Dupre so cogently remarked:

[S.K.’s theology] certainly is not a system, and systemization risks losing the specific character of his thought…. Kierkegaard would have thought it the supreme irony of his life that sooner or later his attack on the system would itself be reduced to a system. And yet, even the best known commentaries have not completely avoided this pitfall.42

We should be reminded that S.K.’s first readers, who read his books as he intended, did not even know the identity of the author of many of the works, let alone have footnotes pointing out that such and such a passage refers to such and such a heartbreak; and the journals actually were a private diary. Not to discount the help that the biographical viewpoint can afford, it is yet the case that S.K. was a thinker with a message and not simply an exhibitionist exposing his own psyche. At least once in a while he should be allowed to speak his piece without having to drag his own vita ante acta around after him.

Seventh, a final principle of interpretation would apply to the study of any writer, but the wide scope of S.K.’s subject matter makes it particularly crucial in his case. Because S.K. offers so much, almost anyone can find in him what he wants. Philosophy has found the wherewithal for several types of existentialism; theology for the array of dialectical theologies; psychology for logotherapy and other “existential” schools. Literature, art, and education have found material for their purposes; and there is no knowing who will yet find what. All this is legitimate, of course, but there is also the dangerous tendency for each variety of scholar to treat S.K. as though he were essentially of the scholar’s particular orientation. Distortion is the only possible result.

Yet, indeed, the present case is nowise different. In the pages that follow S.K. will be portrayed as a Protestant sectary–and that by a student who is himself a church historian, minister, and teacher in the Church of the Brethren, as typical a sect as came out of the tradition. However, I am aware of my bias and so intend to protect myself by following the principles above, as well as the usual canons of research. But biased or not, the view herein presented needs to he considered along with those already in circulation.

| In Dru’s and in Rohde’s selections from Kierkegaard’s journals, the number identifies an entry rather than a page; the date following is that of the particular entry. 1. “The Journals of Kierkegaard, ed. and trans. Alexander Dru (NY: Oxford Un. Press, 1938), 795 (1848). 2. Adolf Deissmann, Paul, A Study in Social and Religious History (first published, 1912), trans. Wm. E. Wilson (NY: Harper, 1957), 5-6. 3. In English, all of this material has been published under the title of the book itself, The Point of View for My Work as an Author, trans. Walter Lowrie, newly edited Benjamin Nelson (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1962). 4. Point of View, 5-6, 9. 5. Dru Journals, 16 (1835). 6. Kierkegaard’s Diary, ed. Peter P. Rohde, trans. Gerda M. Anderson (NY: Philosophical Library, 1960), 202 (1849). The first quotation comes from a point very early in S.K.’s Career, this one comparatively late. 8. Perry D. LeFebre, The Prayers of Kierkegaard (Chicago: Un. Of Chicago Press, 1956), 128; cf. v-vi. LeFevre’s exposition of S.K. is an outstanding effort in becoming consistent with the perspective indicated. 9. Paul L. Holmer, “On Understanding Kierkegaard,” in A Kierkegaard Critique, ed. Howard A. Johnson and Niels Thulstrup (NY: Harper, 1962), 52. 10. Paul L. Holmer, a review of Louis Dupre’s Kierkegaard as Theologian, The Journal of Religion, 63 (1963), 255-56. 11. Niels Thulstrup, “The Complex of Problems Called ‘Kierkegaard,’” in Critique, 295.” 12. Ibid., 295. 13. William Barrett, Irrational Man (Garden City: Doubleday, 1958), 2:69ff. 14. L. Harold DeWolf, The Religious Revolt against Reason (NY: Harper, 1949), 22-54. 15. James M. Edie, “Faith as existential Choice,” in Christianity and Existentialism (Evanston: Northwestern Un. Press, 1963), 37. 16. The central thrust of Edie’s essay is a comparison between S.K. and Tertullian, the previous Christian thinker who, according to Edie, is most like him. 17. Ibid., 38-39. 19. Ragaz, Das Evangelium und der soziale Kampf der Gegenwart (1906), quoted in Ernst Troeltsch, The Social Teaching of the Christian Churches (1912), trans. Olive Wyon (NY: Macmillan, 1931), 1:434. 20. For an account of this Franck-Arnold background, see Ernst Troeltsch, The Social Teaching of the Christian Churches (1912), trans. Olive Wyon (NY: Macmillan, 1931), 1:334, and 2:946ff. 21. Quoted in “Arnold, Gottfried,” The Mennonite Encyclopedia (Scottdale, Pa.: Mennonite Publishing House, 1955), 1:164-65. 22. One of Troeltsch’s major contentions is that, if the sectarian line is to be properly understood and appreciated, the basic typology must be made tripartite and “sectarianism” distinguished from “spiritualism.” His point is well taken, but it need not be taken into account at this point in our discussion. 23. See particularly, Ernst Troeltsch, op. cit., 1:435ff. 24. Ronald A. Knox, Enthusiasm: A Chapter in the History of Religion (New York: Oxford Un. Press, 1950). 25. Emil Brunner, The Christian Doctrine of the Church, Faith, and the Consummation; Dogmatics: Vol. III, trans. David Cairns and T. H. L. Parker (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1962). 26. Ernst Troeltsch, op. cit., 1:334. 27. Ibid., 1:329. 28. Ibid., 1:333. 29. Ibid., 1:158, 282. 30. Ibid., 2:947-48. Troeltsch himself admits the ambiguity within Luther but is not ready to accept the distinction between an earlier and a later reformer. 31. Knox, op. cit., 45. 32. Brunner, Dogmatics, 3:58. 33. Ibid., 73ff. 34. Ibid., 31; cf. 28, 131. 35. Ibid., 74-76. 36. “My Activity as a Writer” (1851) in Point of View, 142-43. 37. Ibid., 133; cf. 97. 38. Point of View, 42. 39. Howard Hong has made this point in his Foreword to Gregor Malantschuk’s Kierkegaard’s Way to the Truth, trans. Mary Michelsen (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1963), 6. 40. “S.K.’s Personal Declaration” in Concluding Unscientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments, by Johannes Climacus (pseud.), trans. David F. Swenson and Walter Lowrie (Princeton: Princeton Un. Press, 1941), 551-52. Cf. Dru Journals, 1238 (1841). 41. Point of View, 39-41. 42. Louis Dupre, Kierkegaard as Theologian (first pub. in Dutch, 1958), (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1963), xii. 43. Ibid., 31, 33. Howard Hong also makes this point in his Foreword to Malantschuk, op. cit., 7. |

II. Where Is True Christianity to be Found?

Whatever of true Christianity is to be found in the course of the centuries must be found in the sects and their like.1

Into what particular church or tradition does S.K.’s religion best fit? Few questions in Kierkegaard scholarship provide quite as much employment as this; perhaps to no other has been proposed such a wide range of solutions. S.K. himself set the stage for the discussion by departing this earth at a moment when the matter of his religious affiliation was somewhat in abeyance. What follows is a survey of the options that are open and which have been argued by various scholars.

A. Atheistic, or at Least Secular, Existentialism

This is a conjecture made from time to time though always as pure conjecture. There are probably two different motives behind it: first, the too-easy assumption that S.K.’s attack on the church actually was (or would have become) an attack upon Christianity itself; and second, the subjective judgment of a thinker who finds S.K.’s “existentialism” appealing but his “Christianity” quite otherwise, who personally feels that the two elements are incompatible, and who thus assumes that eventually S.K. would have dropped his Christianity.2

We call this position “pure conjecture” because, in the first place, it must fly directly in the face of S.K.’s own radically Christian protestations. Second, the position is not (and indeed cannot be) supported with documentary evidence hut only by the “feel” of the critic. And third, modern scholarship generally shows no inclination at all to go this direction. Although no conjecture dare be ruled out as a possibility, this one has little to offer as a perspective from which to view S.K.’s avowedly Christian authorship.

B. Lutheranism, and the Other Reformation “Churches”

Although the question here necessarily devolves on the Danish Lutheran Church of which S.K. was a long-time communicant, this option actually represents the entire “churchly” tradition of Protestantism. No one ever has suggested that S.K. would have been any happier in another established church (i.e. Reformed or Anglican) than he was in Lutheranism. Clearly, S.K. belongs either in Lutheranism or else in an entirely different sort of tradition.

Some of the facts regarding S.K.’s relation to his church should be before us as we consider this alternative:

Alternative 1: S.K. was born, reared, and educated (up to the level of Master of Arts–the equivalent of our doctorate in theology) in the Danish Lutheran Church. Although not ordained, he preached from time to time and was well acquainted with many of the clergy, including the highest officials of the church. His attendance at services was very regular.

Alternative 2: Beginning far back in his authorship, however, first in his journals and then in his published works, there appeared a stream of criticism ever growing both in quantity and in virulence. This will be traced and analyzed in a later chapter, but suffice it to say that the critique centered on the constitution of the church (particularly as regards its relation to the state and the “world”), on the government of the church (particularly as regards the nature and character of the clerical office), and on the sort of preaching that was prevalent in the church.

Alternative 3: Parallel to and a part of this critique was a growing criticism of Martin Luther. Thus S.K. was concerned not only with a “fallen” Lutheranism but traced several of the church’s defects back to the Reformer himself.

Alternative 4: In 1854-1855 this critical development culminated in an open pamphleteering attack upon the church. The literature (which we read under one cover, Attack upon “Christendom”) was as acid as ink can get. The statement that S.K. used as his declaration of intent was published as a separate and independent document, was in formulation for over a year, and continually was quoted from and referred to in S.K.’s subsequent pamphlets. The core of it reads: “Whoever thou art, whatever in other respects thy life may be, my friend, by ceasing to take part (if ordinarily thou dost) in the public worship of God, as it now is (with the claim that it is the Christianity of the New Testament), thou has constantly one guilt the less, and that a great one: thou dost not take part in treating God as a fool by calling that the Christianity of the New Testament which is not the Christianity of the New Testament.3

Alternative 5: S.K. followed his own advice; Hans Brohner, a contemporary who was something of a friend, reported “At the time when Søren Kierkegaard began his polemic against the Establishment, and perhaps for some time before, he had ceased to participate in church services.”4

Alternative 6: Dupre indicates that during the final weeks of his life S.K. actually stopped churchgoers in the street in an attempt to dissuade them from the sin of worshiping in the state church.5 While in the hospital during his final illness S.K. refused a visit from his brother Peter–not because Peter was his brother but because he was a priest6 who had publicly taken the side of the church against S.K.7

Alternative 7: Also, in the hospital S.K. refused communion. The circumstances are instructive. The following conversation was recorded by Emil Boesen, S.K.’s friend from childhood, his closest confidant during the final illness, and a priest. Boesen speaks first:8

Do you wish to receive Holy Communion? “Yes, but not from a parson; from a layman.” That is difficult. “Then I shall die without it.” That is not right! “On that point there can be no argument, I have made my choice, have chosen. The parsons are the King’s officials, the King’s officials have nothing to do with Christianity.”9

Alternative 8: After S.K. died and was thus bereft of any means of defending himself, the church decided that decorum could best he served by “forgiving” him; that forgiveness was the last thing S.K. would have accepted from the church seems not to have come into consideration. He was buried with full ecclesiastical honors, the funeral held before a standing-room only crowd in the cathedral church following Sunday services. Brother Peter, the priest whom S.K. had refused to see a few days earlier, delivered the message.10 But even in the face of this history, considerable scholarship has had the effect of joining forces with S.K.’s ecclesiastical undertakers to put him to rest in the Lutheran Church. Some do it with silence; some do it with a word; some do it with extended argument; it can be questioned whether any do it convincingly.11

In this regard there are two alternative interpretations which should be considered. They both have the net effect of leaving S.K. in the Lutheran fold and thus are enumerated under the heading above:

The Attack as Aberration

This suggestion is that in the Attack of 1854-1855 S.K. had lost control of himself and thus fallen into an extremism which cannot be taken as indicative of the real Kierkegaard, i.e. the S.K. who became disaffected with the Lutheran Church was not one who seriously need concern us. It is interesting that one comes across the rebuttal to this argument much more often than the argument itself; the issue is as good as settled. David Swenson’s judgment is typical: “There are students of Kierkegaard who although otherwise sympathetic, feel that this attack was the expression of something pathological in his nature. Others interpret it as the beginning of a development which would inevitably have taken place, had he lived, in the direction of a modern non-Christian liberalism, perhaps humanism; still others think he would have become a Catholic. To anyone who has read his journals, all these guesses must seem fantastic.”12The Attack is not like the peel of an orange that can be torn off and discarded in the process of getting at the Kierkegaardian fruit. Rather, S.K.’s authorship is constructed like a Spanish onion. It is obvious that the outside, yellow, 1855 layer is of a rather different hue than the innermost, white, 1843 layer. But as easy as it is to make the distinction, just that impossible is it to say where the white ends and the yellow begins. The Attack is an integral part of Kierkegaard and must be treated as such–although, on the other hand, the Attack is not the whole of Kierkegaard (not even the whole answer regarding his religious orientation) and must not be treated as such.

The Attack as Corrective

This proposal, as the foregoing one, solves the problem by eliminating it–but without recourse to as radical a diagnosis as “aberration.” It suggests that the Attack is to be understood as a “corrective.” Now the evidence that S.K. himself so interpreted the situation–and used the very term–is unimpeachable (for example, S.K.’s statement below). The question, then, is: What does “corrective” connote? Is our understanding of the term the same as S.K.’s? The matter has been made extremely elusive in that it has not been discussed as a question; each scholar has taken his own reading of “corrective” and proceeded to apply it to S.K.The general interpretation–more often implied than spoken–is that to call the Attack a corrective means that S.K.’s words and actions had no specific relevance except for Søren Kierkegaard, in 1855, in the nation of Denmark. He had in mind only the staging of a “demonstration” and did not expect or intend that there should result any program of actual reform.13 Neither by directive nor by implication did S.K. mean to propose any sort of norm regarding how other people should live their Christian lives. All he said and did was so exaggerated for the sake of effect that it need not be taken too seriously–or only after having been toned down drastically. Whatever ideas in the Attack seem too radical can be dismissed as “corrective hyperbole.” Of course, no proponent of the view states the matter quite this baldly, but the point gets made one way or another.14 But it can be questioned whether S.K.’s understanding of “corrective” was this one. In introducing the pamphlet series that constituted the major thrust of his Attack, S.K. said, “Yet it is nothing ephemeral I have in mind, any more than it was anything ephemeral I had in mind before; no, it was and is something eternal: on the side of the ideal against illusions.”15

And the fact that he left the church and urged others to do so substantiates his claim to seriousness.S.K. explained what he meant by “corrective”: “He who must apply a ‘corrective’ must study accurately and profoundly the weak side of the Establishment, and then vigorously and one-sidedly present the opposite…. If this is true, a presumably clever pate can reprove the corrective for being one-sided. Ye gods! Nothing is easier for him who applies the corrective than to supply the other side; but then it ceases to become the corrective and becomes the established order.”16

To call a corrective “one-sided” is quite different from calling it “exaggerated,” “transitory,” or “non-normative.” According to S.K.’s explanation, the statements and acts of the corrective still would stand as they are, for what they are. The most that might be done is to supplement them with some other statements, but there is no suggestion that they are to be diluted, deemphasized, or ignored.

Of course, the satire of S.K.’s Attack

is to be read as satire, and the humor is to be laughed at (not, laughed off), but the point behind it all is to be taken just as seriously as it was intended–intended by a man who was willing to cut himself off from the fellowship of the church and, on his deathbed, decline its sacraments for the sake of making that point. The Attack must not be allowed to dominate our study, but it must be given its proper weight–which is to suggest that S.K.’s relationship to Lutheranism was at least questionable.

C. Roman Catholicism

The suggestion that S.K. was essentially a Roman Catholic–at least to some degree and in some respects–is one that has had surprising persistence and strength.17 However, it seems evident that a very real factor in this view springs not so much from evidence within S.K. himself as from a dearth of categories on the part of the analysts. In his writings S.K. was highly critical of “Protestantism”; he often used this term in his critique, and his expositors have followed his lead. Of course, the term “Protestantism” immediately suggests the dichotomy Protestantism/Catholicism; and from this it is an easy step to the assumption that “anti-Protestant” is the equivalent of “pro-Catholic.” But this is an oversimplification; and the Catholic scholar Louis Dupre senses the non sequitur:

One might be inclined to think that, after this vigorous attack on Lutheranism and even on the principle of the Reformation itself, Kierkegaard was well on the way to becoming a Catholic…. Indeed, the principal points on which this view is based are untenable…. If Kierkegaard’s conception of the Church cannot be called the traditional Protestant one, it is even less Catholic. Karl Barth may be right in refusing Kierkegaard a place among the great Reformers of the nineteenth century, but this does not make him a Catholic.18

A close examination will show that in almost every case S.K.’s critique of Protestantism applies directly to the “churchly” tradition within Protestantism but not in the same degree, if at all, to the “sectarian” tradition. If the tertium quid of sectarianism is kept in the picture, and if one keeps alert to the narrower, “churchly” connotation S.K. gave to the word “Protestantism,” then his pro-Catholicism simply disappears. Specific instances will come to attention throughout our study.

But when all the evidence is in it is apparent that there are no solid grounds for calling S.K. a Roman Catholic in any sense of the term; and what is more important, to view him from the Catholic perspective contributes little if anything to understanding the core of his witness and work. Dupre’s conclusion–though stated in his Introduction–is: “[I have come] to the conclusion that [S.K.’s] Existenzdialektik is perhaps the most consistent application of the Reformation principle that has ever been made…. It is precisely Kierkegaard’s fidelity to his fundamentally Protestant convictions which constitutes his value for a dialogue between Catholicism and Reformation.”19

D. Spiritual Atomism–The Christian Life Lived Apart from Any Organized Church

To my knowledge no one ever has proposed this as the Kierkegaardian perspective. It should be given consideration, however, if for no other reason than that it actually was the situation in which S.K. stood at the time of his death–i.e., he was a committed, practicing Christian who, as a matter of principle, refused to participate in the life of any organized, institutional church. Nevertheless it is clear that the atomist position does not represent the culmination and trios of S.K.’s religious thought.20

To say this is not so much as even to imply a conjecture about what S.K. would have done regarding his church membership had he lived some years longer; that is a completely impossible and fruitless line of investigation. We are suggesting only that the tenor and weight of S.K.’5 entire witness make it plain that even his leaving of the church was motivated not by the search for a churchless Christianity but for a truly Christian church.

E. Classic Protestant Sectarianism (Radical Discipleship)

This, of course, is the alternative we intend to support. The present chapter is not the place to open the extensive and detailed motif comparison through which we hope to make our case, and so we now offer only a few preliminary, external, and secondary evidences to indicate that the proposal of S.K. as a sectary is not completely preposterous.

I have not found any scholar who deliberately has named sectarianism as the Kierkegaardian perspective; the best we have are oblique hints and pointers. There is, however, one notable exception to this generalization: sectarianism is mentioned explicitly by S.K. himself? The locus of the following quotation is perhaps as significant as its content. This is the next to the last thing S.K. ever wrote; it is a journal entry dated September 23, 1855; his very last entry is dated the next day; he collapsed on the street on October 2 and died November 4. Might this possibly mark S.K.’s culminating insight into the nature and orientation of his own witness?

In the New Testament is the formula for what it is to he a Christian: to fear God more than men. Herein are all the specifically Christian collisions. As soon as one can he a Christian out of fear of men, yea, when out of fear of men one will dare even to let himself be called a Christian, then is Christianity eo ipso come to naught.

One sees therefore what nonsense it is to believe that true Christianity is found in ‘the church’–in comparison to which the great number Zero is a more Christian spirit than this which is: human mediocrity, brute-man’s faith in … human numbers. No, whatever of true Christianity is to be found in the course of the centuries must be found in the sects and their like–unless the case is that thus to be a sect, or outside the church, is proof of its being true Christianity. But what is found there [i.e., in true Christianity] may be found in the sects and such, the only thing that resembles the Christianity of the New Testament, that is–a sect, which is what it is also called in the New Testament.21

And this was no sudden conclusion on S.K.’s part; he had expressed similar sentiments at least five years earlier, though not in quite such decisive and absolute terms:

The “Establishment” is on the whole a completely unchristian concept. Thus it is ridiculous to hear the Establishment brag itself up in comparison with the “sects”–because there is infinitely more Christian truth in sectarian delusion than in the Establishment’s indolence and drowsiness and inertia. And it is still more ridiculous that the Establishment appeals to the New Testament. Indeed, their Christianity itself was a “sect” (and called such at the time) which had (and here also is its “truth”) an Awakening: this is just how legitimate it is to warn people about the sectaries. But now a sect always has the advantage over the Establishment in that it has truth’s awakening, i.e., the truth that lies in an “Awakening” even if that which the sects consider to be the truth is error and delusion.22

Now, of course S.K. was neither a cenobite nor a Schwämergeist (as, likewise, the classic sectaries were not), but in the 1855 quotation he solidly aligned himself with sectarian non-conformity as against churchly friendship with the world and, in the 1849 statement, with sectarian “enthusiasm” as against churchly decorum. And even earlier he had made a very revealing judgment concerning one particular sect:

The reformation abolished the monastery. Very well; I am not going to say anything more about the reformation having brought secular politics into existence. But now look at Christendom; where is there any Christianity except among the Moravians. But the Moravians are not, in a decisive sense, Christians; their lives are not in double danger. They are simply a more worldly edition of the monastery; men who look after their business, beget children etc. and then, within themselves, also busy themselves with Christianity, briefly this is the religion of hidden spirituality. But the other danger, suffering for the sake of the faith they avoid entirely, they avoid being led into the really Christian situation. There is much that is beautiful in their lives, but their peace is not really Christianity, not in the profoundest sense; it resembles the view that makes Christianity into a mild doctrine of truth.23

Notice that S.K.’s criticism of the Moravians is not at all that of a man of the “church” but of a brother sectary who accuses them of having deserted the cause and made their peace with the world rather than being out getting themselves burned at the stake as their forefathers did. Taken all together, these statements constitute enough evidence to merit serious investigation.

But although Kierkegaard scholarship has not picked up these clues, there have been some partial and even some inadvertent insights. Walter Kaufmann, completely in passing, while giving a list to show the variety of religious orientations represented by the founding fathers of existentialism, calls S.K. “a Protestant’s Protestant.”24

He probably meant nothing more than that S.K. was strongly and staunchly Protestant, but the phrase makes an apt epitome of both S.K. and sectarianism. The sectaries, in many respects, do stand in precisely the same relation to mainline Protestantism as Protestantism does to Catholicism; sectarianism is the reformation of the Reformation, as it has been called.

However, it is Dupre who, via this route, has come closest to our view; all he needs is the word “sectarianism.” In a statement that shows more insight into both S.K. and Protestantism than most Protestant scholars demonstrate, he says:

[S.K.] is a person who kept protesting, who could never accept a Church which had become established, even if on the basis of protest itself. In most instances, the Protestant principle has been abandoned as soon as it has developed itself to the point of becoming a Church. Kierkegaard’s intransigent Protestantism continued to protest; he protested against everything, even against the protest itself…. It is true that Kierkegaard placed himself beyond the pale of the Protestant Church. But he never abandoned the Protestant principle.25

“Protest” may not be the best term to characterize the basic nature either of S.K.’s religious dialectic, “the Protestant principle,” or sectarianism, but given such modification, Dupre’s analysis points toward what we mean in calling S.K. “a Protestant’s Protestant” and also what is implied by Classic Protestant Sectarianism.

A somewhat different approach to S.K.’s sectarian perspective perhaps first was suggested by Emil Brunner, although it has been picked up since by others as well. Brunner–who also calls S.K. the “greatest Christian thinker of modern times”–identifies him as one of the “two great figures of Pietism” of the nineteenth century.26 A recent work which becomes more explicit than anything done earlier is Joachim Seyppel’s Schwenckfeld, Knight of Faith. The focus of Seyppel’s study is Schwenckfeld rather than S.K., but in the process of comparing the two men he proposes Pietism as the link between them: “Whereas Schwenckfeld prepared Pietism, Kierkegaard was raised under its influence.”27 Seyppel then traces the historical path by which German Pietism came into Denmark and into direct contact with S.K.;28 and he makes this very interesting reference to the thesis of E. Peterson:

It is understandable, then, to read in an article on Kierkegaard and Protestantism why some of the Dane’s favorite expressions, like, for example, ‘existence’ and ‘reality,’ should be inexplicable without a reference to the ideas of Pietism.29

Although any direct personal influence from Schwenckfeld to S.K. would have to have been tenuous indeed, the influence from Pietism was not. In fact, S.K. himself affirmed the connection when he said:

“Certainly Pietism (properly understood, not just in the sense that holds apart from dancing and externalities–no, in the sense of that which hears witness to the truth and suffers for it, that hears with understanding that a Christian is to suffer in this world and that the worldly shrewdness which conforms with the world is unchristian)–certainly it is the sole consequence of Christianity.”30

It is not accurate directly to equate Pietism and sectarianism, although clearly Pietism does represent a sectarian-type tendency. The broader category of sectarianism will do S.K. more justice than simply to call him a Pietist, but to have identified his Pietist affinities is a real gain.

But if S.K. was as typical and obvious a sectary as we have suggested and as the remainder of this volume will be devoted to demonstrate, how is it (the question must be asked) that so many competent scholars have been almost unanimously and totally blind to the fact? A number of explanations suggest themselves. In the first place, he lacked the correct external markings, he neither founded nor joined a sect–unless his call for others to join him in leaving the church be interpreted as a tentative step in this direction.

At the same time, S.K. can be quoted strongly to the effect that he had absolutely no desire to found a sect or new church organization. Several factors must be taken into account, however.

Sectarian leaders customarily express sincere reluctance and even resistance to the idea of leaving the church and founding a separate group. They would much prefer to reform the church rather than separate from it. Thus we find cases–such as the Quakers, the Wesleyans, and the early Puritans–in which the sectaries insisted vehemently that they were not separating from the church and in consequence of which the church itself was forced to take as much responsibility in cutting off the sect as the sect did in separating itself from the church.

Perhaps the strongest consideration is the fact that S.K.’s statements to the effect that he had no intention of founding a sect can as well be interpreted to mean that he had no such intention as that he was conscientiously opposed to sects as such. The truth is that any sect of which S.K. was the founder–or even a member (for one cannot conceive of S.K. as one of a group without his immediately becoming the center of the group)–would have had a very poor prognosis of success or even survival. To set up and run an actual institution requires, in addition to an ideology, some practical skills in the way of administration and organization. Of these S.K. had not a trace. Hans Brøchner, who knew him personally, said: “Kierkegaard had not a sense of actuality, if I may use the expression, which, in a given situation, could form a balance to his enormous reflective powers.”31

And S.K. was aware of the problem: “… I am melancholy to the point of madness, something I can conceal as long as I am independent but which makes me useless for any service where I do not determine everything myself.”32

If a sectary, S.K. clearly was one who was constitutionally unfitted to belong to a sect. But this anomaly in no way invalidates our contention or changes the orientation of S.K.’s work. If a sectary, S.K. must be seen not as an organizer but a theoretician (if that term properly can be applied to one so opposed to “theory”). He would well qualify as “the sectaries’ theologian” except for the fact that the sectaries’ theologian hardly qualifies as a theologian. Nevertheless, although this lack of external indicators does not affect the sectarian character of his thought, it has tended to block the discovery that it is sectarian–and thus the possibility has been overlooked.

Another, and perhaps more important, factor in this scholarly blindness is the fact that for most critics the very term “sectarianism” is a bad word, one they would not at all be happy to have associated with S.K. It carries connotations of divisiveness, narrowness, and fanaticism that do not fit well with “the greatest Christian thinker of modern times.” (In due course we shall see that these connotations are not properly a part of the basic concept “sect,” although neither is it entirely accidental that the derogation has adhered to the term.)

Yet it is interesting to note that of the Kierkegaard scholars who approach S.K. from a religious viewpoint at all, nearly every one comes from the “churchly” (and rather high-churchly) traditions. Some of them are Roman Catholics. The Danish and German scholars are, of course, for the most part Lutheran. But even in England and in this country Kierkegaardians have tended to come predominantly from the Catholic, Lutheran, and Anglican ranks. There is an interesting exception; one of the very earliest students and translators of S.K. in America was Douglas Steere, a Quaker sectary; his presence serves simply to prove the rule. But now it is proper that the scope of scholarship be broadened and that S.K.’s thought be examined by those who look from a rather different perspective.

There is a peripheral line of evidence regarding S.K.’s sectarianism which needs to be considered at some point, and better here than elsewhere. It is not sufficient to maintain that a thinker has been understood just because his antecedents have been traced or that he dare be allowed no ideas that cannot be accounted for in his antecedents. However, there are some external findings that may serve at least to make S.K.’s sectarianism historically plausible.

One of S.K.’s nieces reported that both Søren’s father and Emil Boesen’s were members of “the Moravian brotherhood.”33 Just what this “membership” amounted to is a little difficult to ascertain, because it is quite clear that the entire family were also staunch and loyal members of the state church; but the opportunity for Moravianism to influence S.K. was there in any case. Brøhner described the religion of S.K.’s father as “pretty much that of the old pietists.”34

A catalog of the library S.K. left behind him shows something of his interests and possible sources of influence. Both Dru and Croxall list one group of hooks as the “mystics,” but whatever the heading, here is clearly a sectarian style of thought. Dru names the authors: “Tauler, Ligouri, Sailer, Zacharias Werner, Arndt, Thomas a Kempis, Baader, Bernard of Clairveaux, Bonaventura, Ruysbrock, Boehme, Fenelon, Guyon, Swedenhorg, Tersteegen, Lamennais, 22 vol. of Abraham a St. Clara, etc.”35 Apart from duplications, Croxall also lists Suso, Angelus Silesius, and (as significant as any) Gottfried Arnold.36

Much more valuable than these library lists are S.K.’s references to his own reading. In Purity of Heart he quotes from Johann Arndt’s True Christianity37 (although earlier than the Pietist movement per se, this book became a popular handbook of Pietist and other sectarian groups). In one of the Edifying Discourses he calls it “an ancient, venerable, and trustworthy book of devotions.”38 And in a reference which the Danish editors are confident intends Arndt’s book and is a true autobiographical detail, the pseudonym Quidarn wrote in his diary: “The Bible is always lying on my table and is the book I read most; a severe hook of edification in the tradition of the older Lutheranism is my other guide….”39

In Either/Or, Judge William, a pseudonym, quotes Fenelon.40 S.K. himseff later said, “I have been reading Fenelon and Tersteegen. Both have made a powerful impression upon me.”41 And as the motto for a very personal little piece, “About My Work as an Author, “S.K. used a verse from Tersteegen’s Der Frommen Lottrie, another devotional of the sectaries.42

We have made this survey of S.K.’s religious options not so much to close some possibilities as to open one, namely, Classic Protestant Sectarianism. To that investigation we now proceed.

In Dru’s and in Rohde’s selections from Kierkegaard’s journals, the number identifies an entry rather than a page; the date following is that of the particular entry.

1. Søren Kierkegaards Papirer, hereafter referred to as Papirer, ed. P. A. Heiberg, V. Kuhr, and E. Torsting, 2d ed., (Copenhagen: Gyldenalske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag, 1909-1948, 11:2:A:435 (1855) [my trans.-VE.].

2. Among the early Kierkegaardians who at least leaned in this direction, Walter Lowrie names Brandes, Brøchner, Höffding, and Schrempf; see Lowrie’s Kierkegaard (first published 1938) (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1962), 1: 3-6. More recently, Karl Jaspers has hinted at this view–as reported (and discounted) by Walter Kaufmann in his Introduction to S.K.’s The Present Age and The Difference between a Genius and an Apostle (hereafter referred to as The Present Age), revised trans. Alexander Dru (New York: Harper Torchhooks, 1962), 11-12. Colin Wilson also has made the hint; see his Religion and the Rebel (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1957), 239.

3. Attack upon “Christendom,” trans. Walter Lowrie (Boston: Beacon Press Paperback, 1956), 57ff.

4. “Br’chner’s Recollections,” in Glimpses and impressions of Kierkegaard, ed. and trans. T.H. Croxall (Welwyn, Herts: J. Nesbjt, 1959), 38.

5. Dupre, op.cit., 165. He does not cite the source of this information.

6. “Priest” is the term commonly used in the Danish church for its clergymen, and thus it appears extensively in S.K.’s writings. It should not be taken as implying any sort of sacerdotal sarcasm either here or in S.K.

7. S.K. was willing to send Peter a brotherly greeting but did not feel up to receiving him in person. Croxall, op. cit., gives us a letter by the relative who carried the greeting (102, 4) and a statement by Peter (129) which together make it plain that both Soren and Peter realized how the matter stood.

8. Boesen’s account is found in Dru Journals, 551.

9. The primary sources describing the funeral and burial are collected in Croxall, op. cit., pp. 84ff.

10. Of course, any study of S.K.’s religion that fails to raise the question of his church affiliation as much as suggests that he remained a Lutheran. More explicit claims of varying sorts are represented by H. V. Martin, Kierkegaard, the Melancholy Dane (NY: Philosophical Library, 1950), 108; by Hermann Diem, Kierkegaard’s Dialectic of Existence, hereafter referred to as Dialectic, trans. Harold Knight (Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1959), 157; and by Martin J. Heinecken, The Moment Before God (Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press, 1956), pp. 378-79. Our contention is simply that the burden of proof rests just as heavily upon those who would claim S.K. for Lutheranism as upon those who would claim him for Roman Catholicism, secularism, sectarianism, or any other tradition. S.K.’s natural connections with the Lutheran Church do not answer the problem; too many objections must be taken into account.

11. David Swenson, in the translator’s Introduction to S.K.’s Philosophical Fragments, trans. David Swenson, 2d ed., with an introduction and commentary by Niels Thulstrup translated by Howard Hong (Princeton: Princeton Un. Press, 1962), xli-xlii. Cf. Walter Lowrie, in the translator’s Introduction to Attack upon “Christendom,” xiii. Cf. Diem, Dialectic, 154.

13. See, for example, Diem, Dialectic, 157.

14. In addition to Diem, see, as another example, Theodor Haecker, Søren Kierkegaard, trans. Alexander Dru (London: Oxford Un. Press, 1937), 67.

15. Attack upon “Christendom,” p.91.

16. This journal entry has been inserted by the translator into Attack upon “Christendom,” 17. An admirable summary which cites many of the scholars and their claims is Heinrich Roos, S.J., Søren Kierkegaard and Catholicism, trans. Richard Bracken (Westminster, Md.: Newman Press, 1954). Cf. Cornelio Fabro, C.P.S., “Faith and Reason in Kierkegaard’s Dialectic,” in A Kierkegaard Critique, particularly 156-58, 190-94.

18. Dupre, op.cit., 216, 217, 219.

19. Ibid., x, xii.

20. Though not addressing himself specifically to our question, it is perhaps Hermann Diem (Dialectic, 98ff.) who has given most decisive demonstration to the fact that the existence of an organized church with its preaching, doctrine, and sacraments was an essential presupposition of S.K.’s whole dialectic.

21. Papirer, 11:2:A:435 [my trans.–V.E.]. Cf. the trans. Offered by Ronald Gregor Smith in his volume of journal selections, The Last Years, hereafter referred to as Smith Journals (New York: Harper & Row, 1965).

22. Papirer, 11: A:407 (1849) [my trans.–V.B.]. Cf. Smith Journals, 11:2:A:39 (1854) and 11:2:A:39 (1854).

23. Dru Journals, 831 (1848); cf. 1234 (1851).

24. Walter Kaufmann, in the editor’s Introduction to Existentialism from Dostoevsky to Sartre (Cleveland: Meridian Books, 1956), 11.

25. Dupre, op.cit., 224-22. Another inadvertent description of S.K.’s sectarianism is found in Fabro, op.cit., in A Kierkegaard Critique, 156-57.

26. Emil Brunner, Truth as Encounter (Phihidelphia: Westminster Press, 1943 and 1964), 112, 84; cf. 42-43.

27. Joachim H. Seyppel, Schwenckfeld, Knight of Faith (Pennsburg, Pa.: The Schwenckfelder Library, 1961), p.427. Cf, Dupre, op.cit., xi, 171.

28. Ibid., 427-29.

29. Ibid., 129. Seyppel cites E. Peterscn, “Kierkegaard und der Protestantismus,” Wort and Wahrheit 3, 579 ff.

30. Papirer, (through an error in transcription, the locus of this entry has been lost) [my trans.-V.E.].

31. Brøchncr’s Recollections in Croxall Glimpses, 21.

32. Dru Journals, 970 (1849).

33. Henriette Lund’s Recollections in Croxall Glimpses, 50.

34. Hans Brøuchner’s Recollections in Croxall Glimpses, 36.

35. In the Introduction to Dru Journals, 1, note.

36. In the editorial materials of S.K.’s Johannes Climacus, or De Omnibus Dubitandum Est, hereafter referred to as Johannes Climacus, trans. and ed. T. H. Croxall (Stanford: Stanford Un. Press, 1958), 27-28.

37. Purity of Heart, trans. Douglas V. Steere (NY: Harper, 1948), 152.

38. Edifying Discourses, trans. David F. and Lillian Marvin Swenson (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1948), 4:70-71.

39. Stages on Life’s Way, ed. Hilarius Bookbinder (pseud.), trans. Walter Lowrie (Princeton: Princeton Un. Press, 1940), 218.

40. Either/Or, ed. Victor Eremita (pseud.), trans. David F. and Lillian Marvin Swenson and Walter Lowrie, revised by Howard Johnson (Garden City: Doubleday Anchor, 1959) 2:112.

41. Dru Journals, 1220, 443 (1851).

42. In Point of View, 140.

III. Classic Protestant Sectarianism:

In Which a Church Is Not a Church?

Precisely to the concept “Church” is to be traced the fundamental confusion both of Protestantism and of Catholicism–or is it to the concept “Christendom”?1

If S.K. is to be treated as a sectary, it behooves us to be very clear as to what we mean by “sectarianism.” It is not our task to present a full-scale study, but we must pursue the matter far enough to make plain just what we are saying about S.K. when we mount him under the label. This clarification is all the more crucial in light of the various ways the term “sect” is used and misused among us; our concern is as much to establish what we do not intend by the word as what we do.

The “church/sect” typology is the fruit of a half-century of scholarly labors culminating in the work of Ernst Troeltsch in the opening years of the present century.2 Although Troeltsch’s work needs to be modified, supplemented, and reoriented at points, yet in the way of establishing terminology, defining categories, and then analyzing the historical phenomena accordingly, it has not been surpassed. Troeltsch is still indispensable for sectarian studies. Some modern scholars have ignored or belittled him to their own hurt; we shall depend heavily upon him.

The most serious weakness of Troeltsch’s approach is his interpretation of ecclesiology as being essentially a sociological matter rather than an ideological or theological, one. However, as shall become apparent, he was not nearly as guilty in this regard as are some of his successors. He was conscious of the partialness of his perspective and practically invited someone to supplement it:

This theory [the church/sect typology] is connected with a whole series of further distinctions, which belong to the subtler realm of religious psychology and to theological thought…. All this, however, really belongs to the history of doctrine. For our present subject it is vital to remember that the idea of the Church as an objective institution, and as a voluntary society, contains a fundamental sociological distinction.3

Troeltsch was in no sense a socioeconomic determinist; his basic position seems to have been that ideology has sociological manifestations no less than that sociological conditions determine ideology. In fact he went out of his way to insist that the Reformation was essentially a religious phenomenon and not in the first place a sociological one.4 Nevertheless, Troeltsch’s work does show a sociological lopsidedness that requires supplementation if not correction.